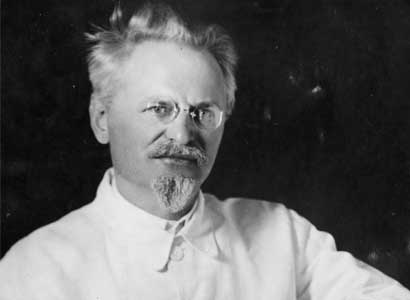

During 1927 Trotsky states that many young revolutionaries came to him eager to oppose Stalin for his having betrayed the Chinese Communists by insisting they subordinate themselves to Chiang Kai-shek. Trotsky claimed: “Hundreds and thousands of revolutionaries of the new generation were grouped about us… at present there are thousands of such young revolutionaries who are augmenting their political experience by studying theory in the prisons and the exile of the Stalin regime.”[73] With this backing the opposition launched its offensive against the Party:

The leading group of the opposition faced this finale with its eyes wide open. We realized only too clearly that we could make our ideas the common property of the new generation not by diplomacy and evasions but only by an open struggle which shirked none of the practical consequences. We went to meet the inevitable debacle, confident, however, that we were paving the way for the triumph of our ideas in a more distant future.[74]

Trotsky then referred to “illegal means” as the only method by which to force the opposition onto the Party at the Fifteenth Congress at the end of 1927. From Trotsky’s description of the tumultuous events during 1927 it seems clear that this was a revolutionary situation that the opposition was trying to create that would overthrow the regime just as the October 1917 coup had overthrown Kerensky:

Secret meetings were held in various parts of Moscow and Leningrad, attended by workers and students of both sexes…. In all, about 20,000 people attended such meetings in Moscow and Leningrad. The number was growing. The opposition cleverly prepared a huge meeting in the hall of the High Technical School, which had been occupied from within. The hall was crammed with two thousand people, while a huge crowd remained outside in the street. The attempts of the administration to stop the meeting proved ineffectual. Kamenev and I spoke for about two hours. Finally the Central Committee issued an appeal to the workers to break up the meetings of the opposition by force. This appeal was merely a screen for carefully prepared attacks on the opposition by military units under the guidance of the GPU. Stalin wanted a bloody settlement of the conflict. We gave the signal for a temporary discontinuance of the large meetings. But this was not until after the demonstration of November 7.[75]

In October 1927, the Central Executive Committee held its session in Leningrad, and a mass official demonstration was staged in honor of the event. Trotsky recorded that the demonstration was taken over by Zinoviev and himself and their followers by the thousands, with support from sections of the military and police. This was shortly followed by a similar event in Moscow commemorating the October 1917 Revolution, during which the opposition infiltrated the parades. A similar attempt at a parade in Leningrad resulted in the detention of Zinoviev and Radek, but Zinoviev wrote optimistically to Trotsky that this would play into their hands. However, at the last moment, the Zinoviev group backed down in order to try and avoid expulsion from the party at the Fifteenth Congress.[76] However Trotsky admitted to having conversations with Zinoviev and Kamenev at a joint meeting at the end of 1927. Trotsky then stated that he had a final communication from Zinoviev on November 7 1927 in which Zinoviev closes: “I admit entirely that Stalin will tomorrow circulate the most venomous “versions.” We are taking steps to inform the public. Do the same. Warm greetings, Yours, G. ZINOVIEV.”[77]

As stated by Goldman, Trotsky’s counsel at Mexico, the letter was addressed to Kamenev, Trotsky, and Y P Smilga. Trotsky explained that, “Smilga is an old member of the Party, a member of the Central Committee of the Party and a member of the Opposition, of the center of the Opposition at that time.” The following questioning then took place:

Stolberg: What do you mean by the center of the Opposition? The executive committee?

Trotsky: It was an executive committee, yes, the same as a central committee.

Goldman: Of the leading comrades of the Left Opposition?

Trotsky: Yes.'[78]

Trotsky stated that thereafter he had “absolute hostility and total contempt” for those who “capitulated,” and that he wrote many articles denouncing Zinoviev and Kamenev. Goldman read from a statement by prosecutor Vyshinsky at the January 28 session of the 1937 Moscow trial:

The Trotskyites went underground, they donned the mask of repentance and pretended that they had disarmed. Obeying the instruction of Trotsky. Pyatakov and the other leaders of this gang of criminals, pursuing a policy of duplicity, camouflaging themselves, they again penetrated into the Party, again penetrated into Soviet offices, here and there they even managed to creep into responsible positions of the state, concealing for a time, as has now been established beyond a shadow of doubt, their old Trotskyite, anti-Soviet wares in their secret apartments, together with arms, codes, passwords, connections and cadres.[79]

Trotsky in reply to a question from Goldman denied any further connection with Kamenev, Zinoviev or any of the other defendants at Moscow. However, as will be considered below, Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev had formed an “anti-Stalinist bloc in June 1932,”[80] a matter only discovered after the investigations in 1935 and 1936 into the Kirov murder.

One of the features of both the first Moscow Trial of 1936 and the Dewey Commission was the allegation that defendant Holtzman, when an official for the Soviet Commissariat for Foreign Trade, had met Trotsky and his son Leon Sedov, at the Hotel Britsol in Copenhagen in 1932. It is a matter that remains the focus of critique and ridicule of the Moscow Trials. For example one Trotskyite article triumphantly declares: “Unbeknown to the prosecutors, the Hotel Bristol had been demolished in 1917! The Stalinist investigators had not done their homework.”[81] Prominent historians continue to cite the supposed non-existence of the Hotel Bristol when Trotsky and his son were supposed to be conspiring with Holtzman, as a primary example of the crass nature of the Stalinist allegations. While Trotsky confirmed that he was in Copenhagen at the time of the alleged meeting, the Dewey Commission accepted statements that the Hotel Bristol had burned down in 1917 and had never reopened. The claim had first been made by the Danish newspaper Social-Demokraten shortly after the death sentences of the 1936 trial had been carried out.[82] In response Arbejderbladet, the organ of the Danish Communist Party, pointed out that in 1932 the Grand Hotel was connected by an interior doorway to the café Konditori Bristol. Moreover both the hotel and the café were owned by a husband and wife team. Arbejderbladet editor Martin Nielsen contended that a foreigner not familiar with the area would assume that he was at the Hotel Bristol.

However these factors were ignored by the Dewey Commission, and still are ignored. Instead the Commission accepted a falsely sworn affidavit by Esther and B J Field, Trotskyites, who claimed that the Bristol café was two doors away from the Grand Hotel and that there was a clear distinction between the two enterprises. Goldman, Trotsky’s lawyer, had stated at the fifth session of the hearings in Mexico that despite the statements that Holtzman was forced to make at the 1936 Moscow trial that he had met Trotsky at the Hotel Bristol, and was “put up” there, “…immediately after the trial and during the trial, when the statement, which the Commissioners can check up on, was made by him, a report came from the Social-Democratic press in Denmark that there was no such hotel as the Hotel Bristol in Copenhagen; that there was at one time a hotel by the name of Hotel Bristol, but that was burned down in 1917…”

Goldman sought to repudiate a claim by the publication Soviet Russia Today that stated that the Bristol café is not next to the Grand Hotel, and used the Field affidavit for the purpose, and that there was no entrance connecting the two, the Fields stating,

As a matter of fact, we bought some candy once at the Konditori Bristol, and we can state definitely that it had no vestibule, lobby, or lounge in common with the Grand Hotel or any hotel, and it could not have been mistaken for a hotel in any way, and entrance to the hotel could not be obtained through it.[83]

The question of the Bristol Hotel was again raised the following day, at the 6th session of the Dewey hearings. Such was – and is – the importance attached to this in repudiating the Stalinist allegations as clumsy. In 2008 Sven-Eric Holström undertook some rudimentary enquiries into the matter. Consulting the 1933 street and telephone directories for Copenhagen he found that – the Field’s affidavit notwithstanding – the Grand Hotel and the Bristol café were located at the same address.[84] Furthermore, photographs of the period show that the street entrance to the hotel and the café were the same and the only signage from the outside states “Bristol.”[85] Again, contrary to the Field affidavit, diagrams of the building show that there was a lobby and internal entrance connecting the hotel and the café. Anyone walking off the street into the hotel would assume, on the basis of the signage and the common entrance that he had walked into a hotel called “Hotel Bristol.” Getty states that Trotsky’s papers archived at Harvard show that Holtzman, a “former” Trotskyite, had met Sedov in Berlin in 1932 “and gave him a proposal from veteran Trotskyist Ivan Smirnov and other left oppositionists in the USSR for the formation of a united opposition bloc,”[86] although Trotsky stated at the Dewey hearings on questioning by Goldman that he had never had any “direct or indirect communication” with Holtzman.

If the statements of Trotsky at to the Dewey Commission and his statements in My Life are considered in the context of the allegations presented by Vyshinsky at Moscow, a number of conclusions might be suggested:

1. From 1925 there was a Trotsky-Zinoviev-Kamenev bloc, or an “Opposition center,” which Trotsky states had an “executive committee; which functioned as an alternative party ‘central committee.'”

2. Although Zinoviev and Kamenev were aligned for a time with Stalin in a troika, they repudiated this in favour of a counter-revolutionary alliance with Trotsky, and spoke at mass demonstrations, along with others such as Radek.

3. Trotsky subsequently condemned Kamenev, Zinoviev et al as “contemptible” for “capitulating,” but Zinoviev, on Trotsky’s own account, was writing to him in November 1928 and warning of what he expected to be Stalin’s attacks.

4. Was the vehemence with which Trotsky attacked Kamenev, Zinoviev and other Moscow defendants a mere ruse to throw off suspicion in regard to a united Opposition bloc, which, according to Rogovin,[87] had been formalized as an “anti-Stalinist bloc” in 1932?

5. On Trotsky’s own account he and Zinoviev, Kamenev, Radek, et al had been at the forefront of a vast counter-revolutionary organization that was of sufficient strength to organize mass disruptions of official events in Moscow and Leningrad, which also had support among military and police personnel.

The only denominator common to Stalin and Putin is rejection of the scheme for world domination of the Anglo-American Satanic societies. Stalin was a hated beast bent on personal survival at the cost of anyone and anything. Putin is a hugely popular nationalist whose sheer nobility drives the ballistic globalists mad with lethal hate. The Goy-hating enemy alien, Khodorkovsky, was busted for trying to sell Russia’s immense Yukos assets to the Anglo-Americans, for brazen high treason. Only Talmudists call Putin Stalinist, and so futilely, so blind to the fact that their world revolution is now impossible given the BRIC superpowers’ emergence. Only Talmudists say Russian media are gagged by tyranny, candidly because media crime is now treated as criminal. This is imcomprehensible to us in the frantic west.

By “Talmudist” read “Evil Jew”. Typical antisemitic drivel, Mike.

No Mark. Most Jews desert Judaism because they refuse to stomarch the lies, filth, unappreasable separatism and the unprovoked malice that sustains the evil institution created in AD30 when the convenant was broken and the veil was rent after a minuscule minority of organised God haters howled, “His blood be upon us an upon our children.” Very few Jews are Talmudist because they reject the defining commandment, “Hate thy neighbour.” One must avoid the “J” word to avoid unjust condemnation of innocent Jews who hate Judaic perfidy and want none of it. And by the bye, “antisemitism” is just a false tag hiding the unmentionable truth that, “No one hates Jews as much as Jews.” (Sarah Silverman)

Rogovin did not claim that anti-Stalin blocs formed in 1932 were only discovered in 1936. If they were, then how is it that the members and sympathizers of the blocs, Smirnov, Ryutin, Uglanov, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Sten, Lominadze, Syrtsov, and others were arrested, exiled, and/or expelled in 1932?

You’re a true master of selective quoting. Bravo.