By 1992, ten years after the height of the killing, the world had caught up to the human rights violations produced by the war, and watch groups began pressing Guatemala’s government to clean up its act. In 1994, with the UN now brokering negotiations, the movement toward peace finally gained enough momentum, which led to peace accords signed on December 29, 1996. The agreement promised fundamental change in Guatemala, including accountability for the murdered and disappeared, recognition and respect for indigenous rights, labor reform, government anti-impunity, education and healthcare, land redistribution, democratizing Guatemala’s political institutions, measures against tax evasion and fraud, termination of civil defense patrols, and army reform.

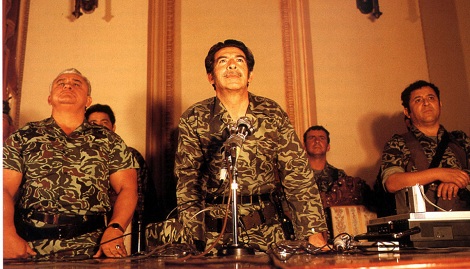

Ríos Montt was elected speaker of Guatemala’s Congress in 1994, and in 1995, seeking the presidency, tried to remove the national election board’s authority to disqualify former coup leaders as presidential candidates. When that failed, he tried to replace the board’s members. When that failed he ran for president anyway and was disqualified. Alfonso Antonio Portillo Cabrera, a close Ríos Montt ally, won the election, campaigning under the slogan, “Portillo the presidency, Montt the power.” “I make the laws of Congress, I approve the budget of Congress, so I already am president,” Ríos Montt would later say.

In 1999, despite the release that year of Truth Commission findings linking him with Army massacres,” Ríos Montt was elected president of Guatemala’s Parliament, with his daughter appointed deputy president and his son head of finances for the Army.

That same year, a plaintiff contingent, frustrated by stalling in Guatemala’s legal system, brought the case against Ríos Montt before the Spanish National Court (SNC) through the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) in San Francisco. Following months of witness testimony, the SNC issued international arrest warrants for Ríos Montt and seven other high-ranking officials on charges of systematic torture, terrorism, and genocide, and ordered their extradition before the SNC prosecutor in 2006. But Guatemala’s Constitutional Court declared the warrants invalid, claiming that the SNC is without jurisdiction in Guatemala.

But a 2001 lawsuit filed by the Association of Justice and Reconciliation and the Centre for Human Rights Legal Action against the core high-command in the 1982-83 massacres finally began bearing fruit. The action accused Ríos Montt, his Minister of Defense, Oscar Humberto Mejía Victores, and his Chief of Army, Hector Mario López Fuentes of genocide in the rounding up and slaughter of Ixil Mayans. Ten years later, in June 2011, López Fuentes was arrested on charges of genocide and forced disappearances, and in October came indictments against Mejía and also against José Mauricio Rodriguez Sánchez, Ríos Montt’s Director of Intelligence, for the same crimes. Two months later, on January 26, 2012, Judge Flores implicated Ríos Montt in the Ixil slayings.

Meanwhile, Guatemala continues to struggle with the effects of the civil war. There is still no rule of law or system of real justice, and the country has gone on to become one of the most violent in the world, with a murder rate five times the global average. Crime gangs have formed and operate with terror tactics similar to those used by death squads during the war. Ninety-eight percent of the country’s crimes go unpunished, and this has made it a haven for drug traffic and organized crime. Low wages create a situation where officials are easily bribed, which makes truth and justice difficult. Rape, torture and murder of females in particular have risen sharply since the war. Hunger and poverty have reached record levels, and Guatemala now has Latin America’s worst malnutrition rate for children five and under.

The 1996 peace agreements have done little to alter Guatemala’s culture of repression and discrimination. Workers’ rights have regressed and employers continue their murder and persecution of unionists. Guatemala’s government still tends toward force and violence to resolve social issues and answer shows of protest. The government still favors the interests of transnationals over the welfare of its people and its environment, granting mining, oil, natural gas, hydroelectric, telecom and transportation licenses to foreign operators in exchange for commissions, which the affected regions see none of.

Most significant, land distribution remains unchanged as the backbone of Guatemala’s problems. Legislation to widen land access and to aid small farmers has been blocked by large landowners, who view it as another start of land reform. The right to “land and clean water, and the promotion of economic, social and labour policies and food security” proposed by recent legislation was defeated again in Parliament, owing to the power of Guatemala’s landed class.

Guatemala is one of several Latin American nations where U.S. intervention has brought disorder and dysfunction. In many ways its story is every Latin American nation’s story: the enfranchised rich cry out when the marginalized try to encroach on their holdings, the U.S. intercedes to protect its interests, a revolution is squashed, and the country languishes as a repressive, kept republic. Panama, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua have each been interfered with, and are among the most backward in the hemisphere, each listing the highest rates of poverty, malnutrition, illiteracy, early mortality, inflation, crime, and corruption.

Dictatorships have left ugly scars on the face of humanity and they have to be cleared sooner than later in order to revive the original beauty of the real human face. The process must get accelerated to emancipate people of the clutches of usurpers of power. The hypocrite champions of human rights, like the US in this case due to whom this inhuman atrocity was carried out, will be unmasked and it will become easier to rid the people of the world of their evil designs,influence and role which has distorted the world to an unacceptable level making it a very dangerous place to live. To achieve this ideal goal, we all must join hands to ensure the fundamental human rights to all the people, irrespective of their race, religion,etc.