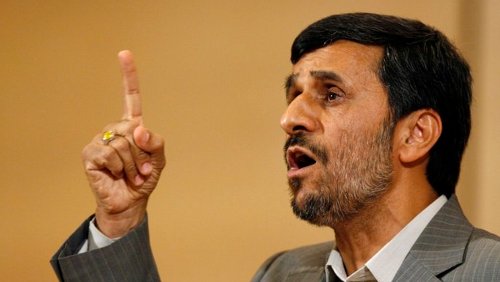

The view from the United States appears to be that, with a Mousavi win on Friday, relations between Iran and America will improve. Mousavi clearly strikes a more conciliatory tone when discussing international affairs than does Ahmadinejad, who has always been consistent in his insistance that Iran has every legal right to enrich uranium under the protocols of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and that sanctions against Iran imposed by U.N. Security Council resolutions are themselves illegal.

“Our country was harmed because of extremist policies adopted in the last three years…My foreign policy with all countries will be one of detente,” Mousavi said after first announcing his candidacy. “We should try to gain the international community’s trust while preserving our national interests.” He has also said, “In foreign policy we have undermined the dignity of our country and created problems for our development.”

Nevertheless, the former prime minister insists that “Iran will never abandon its nuclear right” and echoes the statements of both Khamenei and Ahmadinejad when saying, “If America practically changes its Iran policy, then we will surely hold talks with them.”

It is clear that an electoral victory for Mousavi would be seen as a political victory for Barack Obama as well. It is assumed that Mousavi is more “rational and reasonable” than Ahmadinejad and would therefore be more amenable to Washington’s demands, regardless of how illegal and hypocritical those demands may be. As such, he is the preferred candidate by Western analysts and politicians.

But how different would the United States treat Iran, really?

Back in 2003, soon after the invasion of Iraq, the Iranian government sent a “proposal from Iran for a broad dialogue with the United States” and the fax suggested everything was on the table – including full cooperation on nuclear programs, acceptance of Israel and the termination of Iranian support for Palestinian militant groups.” Flynt Leverett, a senior director on the National Security Council staff at the time, described the Iranian proposal as “a serious effort, a respectable effort to lay out a comprehensive agenda for U.S.-Iranian rapprochement.” A Washington Post report from 2006 revealed that the document listed “a series of Iranian aims for the talks, such as ending sanctions, full access to peaceful nuclear technology and a recognition of its ‘legitimate security interests.’ Iran agreed to put a series of U.S. aims on the agenda, including full cooperation on nuclear safeguards, ‘decisive action’ against terrorists, coordination in Iraq, ending ‘material support’ for Palestinian militias and accepting the Saudi initiative for a two-state solution in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The document also laid out an agenda for negotiations, with possible steps to be achieved at a first meeting and the development of negotiating road maps on disarmament, terrorism and economic cooperation.”

The proposal was roundly rejected by the Bush administration.

The then-government of reformist Iranian President Mohammad Khatami – now a Mousavi supporter – even voluntarily suspended uranium enrichment from 2003 to 2005 and still received nothing but lies and threats from the United States and its European allies. As Ahmadinejad recently pointed out, “There was so much begging for having three centrifuges. Today more than 7,000 centrifuges are turning,” and then asked, “Which foreign policy was successful? Which one created degradation? Which one kept our independence more, which one gave away more concessions but got no results?”

Many commentators point to a new approach from Barack Obama’s Washington, which they believe should be reciprocated from Tehran. Apparently, Obama’s recent Cairo speech appealed to many Iranians, even government officials. Ali Akbar Rezaie, the director-general of Iran’s foreign ministry’s office responsible for North America commended the new tone coming from the US president, saying, “Compared to anything we’ve heard in the last 30 years, and especially in the last eight years, his words were very different… People in the region received the speech, from this angle, very positively, with sympathy.” He added that the upcoming Iranian election would set the stage for a new chapter in US-Iran relations. “After the election we will be in a better position to manage relations with the United States,” he said. “We’ll be at the beginning of a new four-year period, and the political framework will be clear.”

But what has Obama said to or about Iran that should prompt such positive and optimistic responses? Not a whole lot.

Exactly one year to the day before his Cairo speech, and the day after clinching the Democratic nomination for president, Obama stood before the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and stated that “There is no greater threat to Israel — or to the peace and stability of the region — than Iran.” He said this about a country that has not threatened nor attacked any other country in centuries and harbors absolutely no ambitions of territorial expansion. The same can obviously not be said about Israel, or the United States. Obama continued,

The Iranian regime supports violent extremists and challenges us across the region. It pursues a nuclear capability that could spark a dangerous arms race and raise the prospect of a transfer of nuclear know-how to terrorists. Its president denies the Holocaust and threatens to wipe Israel off the map. The danger from Iran is grave, it is real, and my goal will be to eliminate this threat.

Obama threatened Iran with ratcheted up pressure, if it did not bend to American demands – demands based on unfounded accusations and outright lies. This pressure would not be limited to “aggressive, principled diplomacy” but would include “all elements of American power to pressure Iran.” Just to be clear, Obama promised his audience to “do everything in my power to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon.”

In his inaugural address, Obama seemed to calm down and offered the Muslim world “a new way forward, based on mutual interest and mutual respect.” A week later, during an interview with Al Arabiya TV, the new president reiterated his insistence that the US was now “ready to initiate a new partnership [with the Muslim world] based on mutual respect and mutual interest.”

Two months later, in March, Obama addressed the Iranian people and government directly by releasing a taped message on the occasion of the Iranian New Year. The message urged a “new beginning” in diplomatic relations. Obama said,

My Administration is now committed to diplomacy that addresses the full range of issues before us, and to pursuing constructive ties among the United States, Iran, and the international community. This process will not be advanced by threats. We seek, instead, engagement that is honest and grounded in mutual respect.

Obama’s emphasis on “mutual respect” is striking considering the near constant usage of that phrase in Iranian overtures for years. Many Iranian officials, including U.N. ambassador Javad Zarif, former president Rafsanjani, and Foreign Ministry spokesman Hamidreza Assefi, have been calling for international relations based on “mutual respect.” The Mossadegh Project‘s Arash Norouzi points out, as far back as February 2000, then President Khatami was saying, “We believe in existing alongside, and forging relations with, all countries…on the basis of mutual respect and interests.” Then, in early 2004, then Foreign Minister Kamal Kharazzi said, “We call for positive and constructive dialogue on the basis of mutual respect.” In December 2007, Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki stated, “As senior Iranian officials have reiterated, we welcome any rational approach that is based on mutual respect.”

Look at this relibale poll which predicted a landslide victory for Ahmadinejad before 12 June 2009.

The polls show that it is highly possible that the result of the Iranian election 2009 is correct.

The 27% could go to any direction!

Ahmadinejad: 34%

Did not know: 27%

Mousavi: 14%

Karroubi: 2%

Rezai: 1%

See the link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WSH8-LYJ9nM