Just down the road from the Cambodian Landmine Museum is a killing field where an estimated 3,000-4,000 people were killed by the Khmer Rouge. A temple was built directly over the mass grave. A monastery rests to the side, where a twenty-two year old monk, named Sina told me, “We say a special prayer for the people every year.” In the center of the complex is a tall stupa filled with human skulls and bones. The sheer weight, the mass of 3,000 people is staggering. The thought that so many bones and so many shattered lives rest beneath this otherwise serene local is heart-wrenching.

I have lived among the Buddhists, studying and praying with them for years. Although I remain Catholic, I still have a tendency to believe some of their karmic concepts. The people who died here most have been terrified. After years of starvation, torture and hardship, their obedience was rewarded with execution. It almost stands to reason that this place, and maybe every inch of Cambodia, would be teaming with angry spirits.

“Yes, I believe,” agreed Sina. “I have never seen them with my eyes, but people here are afraid of the ghosts. The face of the ghosts is never good. When they see the ghost it is not good. Especially when they are sleeping and they think about ghosts.”

Travel agents in Phnom Penh were able to give me brochures about Disneyland, the City of New York, and the casinos in Las Vegas. They didn’t, however, have any information about the American Indian Genocide Museum. Travel agents in other countries might have information about Auschwitz, but October Fest seems to draw the most tourists to Germany.

Many countries have survived wars and genocides. But what if you were from a country, where the second largest tourist attraction was the genocide museum? And what if that museum was located in the original prison, where thousands of your fellow countrymen were slain? Taking it several steps further, what if every person in your country, over the age of twenty-four, was either a victim or a perpetrator of what has often been referred to as the world’s only auto-genocide? And, what if victims, torturers, and executioners all lived side-by-side, in the same community? This is Cambodia.

Toul Sleng Prison, also called S-21, is the name of the Cambodian Genocide Museum, and it is one of the largest tourist attractions, after Angkor Wat. Under the French, the building had housed Public School 21. After the Khmer Rouge outlawed education, the school was converted to a torture and confession center for Khmer Rouge members accused of treason against Angka, the Khmer Rouge political organization. Prisoners were subjected to the most inhumane torture until they finally broke, at which point they would sign erroneous confessions. One of the more common confessions was being a member of the CIA or KGB. The fact that many of the agents were aged 12-15 and had no idea what the CIA or KGB were was of little consequence. The confession was all that mattered. After the confession, the prisoner was executed. The bodies were dumped in mass graves at a site later called The Killing Fields Cambodia’s third largest tourist attraction.

During the four years of the Khmer Rouge regime, more than 12,000 Khmers were tortured and executed in the prison. More than 2,000 of them were children.

Only seven former inmates of Toul Sleng prison survived. To date, only two remain alive, to serve as witnesses if the Khmer Rouge Trials ever actually take place. As a side note, only two former Khmer Rouge have ever been imprisoned for their crimes against humanity.

Vann Nath, the painter from Toul Sleng, is the most famous survivor, one of only seven. His horrific paintings of Khmer Rouge torture remain on display at the prison, and serve as a haunting testament of man’s inhumanity to man.

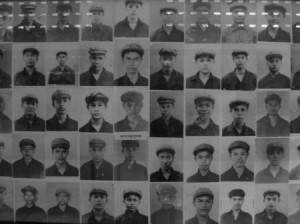

Perhaps one of the most frightening aspects of a visit to S21 is seeing how detailed and how organized the slaughter was. The Khmer Rouge photographed every prisoner, and refused to execute them until after they had signed a confession. Many of these photos remain on display at the museum. The look of fear on the faces of the victims as well as the obvious youth of many, stirs up deep emotions of revulsion and anger. The question “WHY?” reverberates through your mind as you take in the hundreds of portraits of the dead. Even worse is the knowledge that these photos represent a small fraction of the total number of lives which were stamped out in the name of an insane ideology.

My friend, famed combat photographer, Richard Butler, after visiting S 21 for the first time, said, “Primo Levi said of Auschwitz: people doing that kind of crime do it so that no one can tell them it was a mess. As if they wanted someone, after the fact, to say that they had done a good job.” He added, “Maybe that kind of documentation separated them from what they were doing here, and made it just another corporate work assignment.”

“As soon as we read the placard in the front, which tells the basic story of the museum, we began talking about our grandparents and the Second World War,” said Heike, a German student, who I met while she was on a visit to the prison with a group of friends.

“But Hitler was different,” said Arnt, Heike’s classmate. “Hitler hated a defined list of people; Jews first, but also gypsies and gays. With Hitler, you knew if you were on the list or not. But with the Khmer Rouge anyone was a target at any time.”

Some Khmers were killed for being capitalists or intellectuals. But many were killed for no discernable reason at all. The vast majority of Khmers were not killed in the more than 140 prisons located around the country. They were murdered in the villages where they lived, and in the rice fields where they worked.

In Europe, many have raised the question of who, apart from the Nazi soldiers or the leaders, bore guilt. But in Cambodia, such deep-piercing questions need not be asked. In Cambodia anyone could have been a Khmer Rouge, and could have killed or been killed. As Richard put it “Every single Khmer either has blood on his hands, saw his family killed, or both.”

“When we were in Germany planning this trip, we thought of Angkor Wat,” said Heike. “We didn’t think of S-21.” Heike looked around at the dusty, cold stone buildings, most likely remembering the thousands who were systematically executed there. “We didn’t know that humans could behave in such a way.”