Another Narrative: the Asia Foundation Survey for 2010:

The Asia Foundation 2010 survey collected survey information in the same regions as DIAG efforts, and although this article attempts to avoid these separate metrics in linear causality logic, some general conclusions on base assumptions in Coalition disarmament and reintegration logic do become evident. Afghan perceptions of whether they fear for they own personal safety or security within the same regions where DIAG disarmed and disbanded illegal groups ought to have more than a causal relationship due to the underlying logic of the disarmament program. Taking weapons from illegally armed groups ought to reduce violence and improve security. Yet the Asian Survey results for the same aforementioned where DIAG seizure metrics were highest are problematic. The central region (termed Central Hazarjat by the Asian Survey) did reflect a high correlation of ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ responses with 78% of Afghans polled in the region where DIAG weapon seizures were highest in 2010.[17] This supports Coalition disarmament logic and reinforces the program’s narrative. However, the same central region features some of the lowest population density outside of the Kabul Capital region and low insurgency activity as The International Crisis Group reported in 2011.[18] Other regions demonstrate higher levels of security fear that potentially marginalize the DIAG linear causality of ‘disarmament leads to greater security.’

Central Kabul, with is included in the DIAG’s highest weapon seizure region of ‘central’ with 3,759 weapons in 2010, featured 50% of Afghans polled on security responding that they either ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ feared for their own personal safety.[19] In the region with the second largest DIAG totals in 2010 illegal weapons seized, the south west and south east had the highest fears for security with 55% and 61% respectively responding with ‘often’ or ‘sometimes.’[20] Once again, it would be reckless to correlate the narrow metrics of two separate surveys (DIAG and the Asia Foundation) without becoming anecdotal in nature. Instead, the narrow metrics of the DIAG and the linear causality of ‘weapons-centric’ logic are questioned on whether Coalition forces are critically thinking about disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of illegally armed groups and militias in Afghanistan in 2011. Taking away illegal weapons is certainly an example of treating a symptom, but does it ever get to any root problems facing Afghanistan?

Recent efforts through the Afghan-led ‘Peace and Reintegration Program’ has also been difficult to measure, with local Afghan leadership telling Coalition leadership to have patience while they negotiate and offer economic incentives in the form of international donations to armed fighters. As International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Director of the Force Reintegration Cell British Major General Phil Jones stated in a recent DOD news briefing, “This is a historical phenomenon in Afghanistan anyway; sort of over the years, people come and go into the insurgency. The trick here is to really try and make sure that they stay out of the fight for good and make it an enduring solution.”[21] Afghanistan demonstrates that after over three decades of constant warfare, weapons exchange hands as often as allegiances and motives to fight; yet Coalition fixation on weapon-centric metrics may only be influencing the short-term symptoms associated with economic seasonal cycles and ignoring the deeper long-term problems that perpetuate Afghan instability over years. Since the late 19th century, Afghan rulers have struggled to break the endless cycle of Afghans entering and leaving military service and criminal militia organizations. From the age of Afghan Kings through the Soviet period and during the Taliban era, generations of Afghan military-aged males have been armed, disarmed, recruited, lost, and later recruited by a rival for continuous violence and instability.[22] Guns are symptoms of deeper issues, yet the DDR, DIAG, and APRP programs appear to fixate too much on the former instead of the latter.

How Design and Critical Thinking Frame the Problem Differently:

If seizing weapons and disarming illegal groups demonstrates metrics that are only partially linked with understanding how a complex system such as the Afghan counter-insurgency and criminal environment functions, how can Coalition forces and their Afghan partners better accomplish strategic goals?[23] The remainder of this article applies U.S. Army ‘design theory’ to critically think and creatively apply deep understanding and holistic appreciation of the Afghan system beyond the linear causality of ‘seizing weapons and disarming illegal groups improves security.’[24] ‘Army Design Methodology’ represents a different method of thinking about and making sense of complex problems that military organizations often face in the modern post-Cold War era. Instead of focusing on categorizing, reducing, and describing a problem, Design attempts to understand complex systems holistically, seeking explanation instead of description. Design nonetheless remains a controversial and often misunderstood methodology for military planning, and this article is another attempt at demonstrating the value in considering the Design approach.

Drawing from a previous Design exercise on the topic of Mexican drug cartels and criminal enterprise, this article proposes that Afghanistan values and rule of law in relation to tensions between ‘valued’ and ‘not valued’ provide a highly abstract framework for Afghan system behavior.[25] A higher level of abstraction is often useful to help make better sense of a complex system from a holistic perspective. In other words, “to be a successful generalist, one must study the art of ignoring data and of seeing only the ‘mere outlines’ of things” according to General Systems Theorist Gerald M. Weinberg.[26]

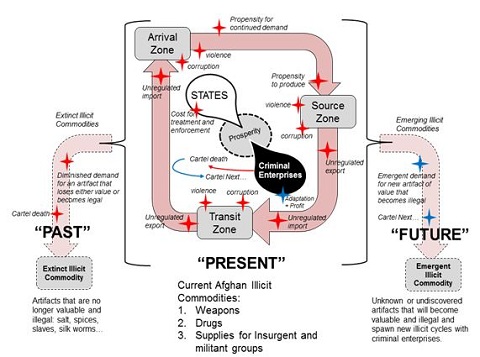

Essentially, figure 1 below applies a quad-chart where the dueling tensions of ‘value’ and ‘legality’ explain how criminal enterprise such as drug smuggling, corruption, black-market activity, theft, and insurgent violence self-organize and adapt based upon persistent and societal forces.

Figure 1 provides one way to conceptualize the highly abstract processes within Afghan society where some things (or artifacts) are valuable and legal, and other artifacts are deemed illegal by the government and society yet remain valued. In this concept, artifacts in the Q2 quadrant drive the Afghan legal economy and represent all legitimate local, regional, and national business as well as international commerce and trade. Q2 triggers adaptive trade and innovation in rival business development; competition and wealth for success drives continued adaptation. The Q4 quadrant provides explanation that is relevant to the DIAG program as well as counter-narcotics programs for Afghanistan, Afghan Anti-Crime Police, and other relevant agencies that target criminal enterprises that self-organize and adapt.

By self-organization, this means that when artifacts such as opium, AK-47s, or stolen Afghan military uniforms become valued (high demand) yet illegal items, criminal enterprises spawn automatically to profit from delivering the item. Since delivering illegal items requires violation of Afghan law and penetration of physical terrain to deliver to the consumer, these criminal enterprises employ constantly evolving applications of corruption and violence in order to profit from providing the illicit commodity to the willing consumer. In other words, when disarmament efforts in 2010 seized 7,929 weapons, the elimination of the illicit commodities might have artificially created a potentially stronger market for any criminal enterprises that profited through smuggling weapons to regions with high confiscation rates. Disarmed yet unemployed militants become prime targets for regional influences such as Iran, and black market weapons profiteering adapt to local demands.[27] The same could be said for opium, or any other illicit commodity seized yet in high demand within Afghanistan or the global market (opium).[28]

Don’t beat about the bush. What you are really saying is that the US and NATO are trying to buy off those who are opposed to the invasion and occupation of their country. This idea is as old as the hills and even thought it may work for a while it never solves the problem of getting rid of who believe they have the right to take over other people’s countries.