Pakistanis make their anger with the American policies very clear

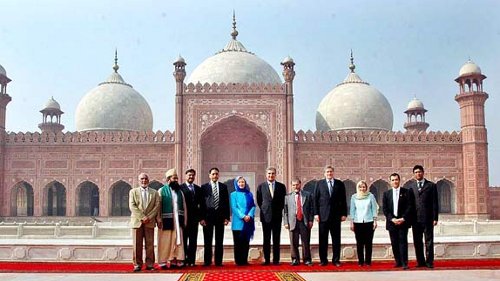

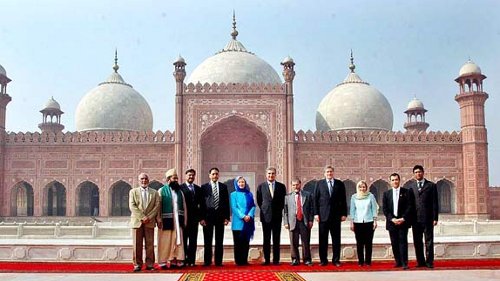

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in a group photograph at the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, Pakistan (APP)

After three days of America-bashing that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton endured during her recent visit to Pakistan, she is sure to have carried back interesting baggage: some realistic and troubling assessments about how Pakistanis look upon the war on terror that America has imposed on them. If she is honest, she will report to President Obama the disdain that exists in the Pakistani streets for America’s thoughtless policies and heartless actions that have brought death, destruction and suffering to the people.

This sentiment could best be gauged by a comment that she heard from a tribesman from FATA, the tribal region straddling Pakistan and Afghanistan where Pakistan Army fights anti-Pakistan Taliban (to be distinguished from Afghan Taliban) and where American drones kill hundreds of women and children, when he said to her point blank, “Your presence in the region is not good for peace.”

Clinton was here for first hand assessments of ground realities important for Obama’s future Afghan war strategy now under review. She wanted to know the mood of the people, the prospects of Zardari’s survival amid public uproar against him on a variety of issues and reading the mind of Pakistan’s military which deeply influences defense and Afghanistan related decisions.

Washington has, in the past, turned a deaf ear to sensitivities and opinions from Pakistani civil society and the media about its heavy-handed, counter-productive, insensitive policies that generated distrust, anger and eventually hatred for America. The Obama administration, like others before it, relies for decision-making on Washington-based neoconservatives, military hawks, war mongering intellectuals, diplomats and so called “experts” who are either unaware of ground realities, or hide unpleasant facts by telling the administrations what they want to hear or perpetuating their own distorted visions. As a result, America lost the hearts and minds of the people. This visit was therefore a breath of fresh air.

Clinton later told CNN that she anticipated the “pretty negative situation” in Pakistan, but she said “I wanted to have these interactions. … I don’t think the way you deal with negative feelings is to pretend they’re not there …”

She was absolutely right. She did well to broaden the scope of her visit by meeting a cross section of civil society. Even though she was sheltered from adverse public opinion and the participants were carefully screened for every forum, they challenged her on sensitive issues such as drone attacks, the mammoth new embassy, suspicious activities of Blackwater now believed by many to be behind devastating bomb attacks, violations of local law by American marines, American plans of denuclearizing Pakistan, its support to anti-Pakistan elements in Afghanistan and FATA, its collusion with India, etc. While she did give forthright answers to some, to many an awkward and probing question Clinton had no answers. “[T]his issue is between the leadership of two sides. So let’s not to discuss this here,” was her typical line.

When Clinton sought support for the Afghan war, in no uncertain terms was she told by a female journalist: “We are fighting a war that is imposed on us. It’s not our war. It is your war. You had one 9-11. We are having daily 9-11s in Pakistan.”

In a country where 90 percent of the people oppose this war, where the Afghan Taliban are regarded as national resistance to the American occupation, and where the fallout of the war turns their lives upside down, this answer is perfectly legitimate. As polls indicate, religious extremism generally enjoys no support and Al Qaeda is not believed to cause bloodshed. The belief is that the American sponsored militants commit these heinous crimes which are then pinned on Al Qaeda. “Winning the hearts and minds of the people is critical for Al Qaeda to succeed. Why then would it shed blood and alienate people”, asked a tribesman.

And when her contention that the U.S. and Pakistan face a common enemy in “terrorism” was publicly rejected, Clinton admitted that “we’re not getting through.”

The critical coverage that American policies received in the media made a frustrated Clinton retort that the US would respond “aggressively” to the misreporting by Pakistani media, drawing an immediate response from the media’s spokesperson who said: “We should understand the actual message behind her statement. The aggressive response means the US will either hit or oblige the media… both are unacceptable to us”. Richard Snelsire of US embassy in Islamabad quickly issued a statement that Clinton was not making any threats. “It has been taken wrong. The word aggressive doesn’t mean that US will take any action…”

Aside from other functionaries, Clinton also met General Kayani, Pakistan’s Army chief. The general’s influence on decision making by the presidency is well understood. Also, the Pakistan Army is the custodian of the country’s nuclear assets, the seizing of which is widely believed to be America’s key objective. The meeting was aimed to figure out General Kayani’s response to an upcoming war strategy in which Obama would most likely want the Pakistan Army to play a role and understand the security environment. She must have also tried to make sense of President Zardari’s position in view of the increasing confrontation that Zardari faces from the Army on security issues.

Zardari and his team, who touted the insensitive piece of American legislation called the Kerry-Lugar Bill (now Act), which drew universal scorn from within the country, were openly rebuffed by the Army when it publicly called upon them to seek a review of clauses unacceptable to the armed forces, after behind-the-scene messages were ignored. These clauses had set off alarm bells in the armed forces over Washington’s demand for indirect veto power over promotions and appointments to senior ranks, something no sovereign nation could allow.

A female National Assembly member, Marvi Memon, who refused to meet Clinton, said in an open letter: “there are patriotic Pakistanis who will defend the soil before accepting your policies of creating a US fiefdom in Pakistan. As a young parliamentarian, I would only welcome you to Pakistan once we have evidence of your shift in policy so that Pakistan is dealt with as a sovereign country.”

In her meeting with prominent tribesmen in the North West Frontier Province, which bears the brunt of the Afghan war, she heard the same hostile message: Pakistanis do not want American friendship despite a multi-billion-dollar aid package laden with insulting conditions.

Clinton’s earlier criticism of Pakistan’s failure to get Al Qaeda leadership had generated negative headlines. Softening her tone, she told a group of women: “What I said was I don’t know if anyone knows, but we in the U.S. would very much like to see the end of the Al Qaeda leadership. And our best information is that they are somewhere in Pakistan, and we think it’s in Pakistan’s interests, as well as our own, that we try to capture or kill the leadership of Al Qaeda.”

But Clinton’s call to locate and eliminate Al Qaeda leadership was rejected. On the contrary it raised some questions: Why after seven years of disinterest in eliminating Al Qaeda leadership by Bush has the Obama administration taken up the cudgel now? Is he seeking in this an objective, which he has been accused of not having in fighting this war? Why is America, with its technology and intelligence, incapable of pinpointing the location of Al-Qaeda leadership to Pakistan? Is Al Qaeda being used as a pretext to launch attacks in Balochistan like 9/11 and Afghanistan?

Pakistan has consistently denied Al Qaeda leadership’s presence on its soil and has challenged the Americans to point it out if they believe it is here. So far no information has been provided.

Anne Patterson, the intemperate US Ambassador in Islamabad in “her imperial hubris” (to borrow a phrase from Eric Margolis) recently called for air attacks on Al Qaeda leaders in Quetta that lends credibility to the belief that America intends to destabilize Balochistan after having done that to FATA and NWFP. There is strong evidence that, with American nod, the Indians are actively supporting Balochistan Liberation Army, a rogue insurgent outfit headquartered in Tel Aviv, with fundraising address in Washington.

Interestingly, when during her televised press conference Clinton remarked “Al Qaeda is in league with the people who are attacking Pakistan,” a young student turned to his friends and asked, “Has the US changed its name to Al Qaeda?”

If Clinton kept an open mind and made some sense of the blunt criticism she heard, she should have drawn some important conclusions. One, there is enormous pent up anger against decades of manipulative American policies to exploit Pakistan. Two, Pakistanis intensely dislike American intervention in its internal affairs, including manipulations of removing and installing governments. Three, no government in Islamabad can survive for too long that serves as a door mat for the Americans, much less the feeble, subservient and extremely unpopular lot that currently runs the government. Four, Pakistanis deeply suspect American intentions and would aggressively reject American diktat that serves its geopolitical interests in this region at the cost of Pakistan’s stability and security.

A debate is still going on whether the war Pakistan fighting in tribal areas is its own or someone else’s. They must know review the situation of Swat to get the answer. It was indeed very comforting information that Swat has almost returned to normalcy. The people of Swat have had a sigh of relief after a long time as schools reopened; trading activities revived and the region of terror came to screeching halt.

The agenda of the perverted mindset of religious extremists was already in place even before the American intervention in Afghanistan. The fuel to the fire was, however, added when the operation took off in Afghanistan and in the tribal areas of Pakistan. The terrorist were organized, funded and equipped by external anti-Pakistan forces to weaken and destabilize Pakistan.

The terrorist forces would have established their own tyrant rule in the tribal areas if the aremed forces of Pakistan had not launched a full fledged operation. In my view this operation should have been launched even earlier, when the extremists had paralyzed everything in different parts of tribal areas. Swatis and a majority of tribal people are patriotic, forward –looking and moderate, and they deserve peace, security and support to have dignified life which hitherto was denied to them by the extremists.