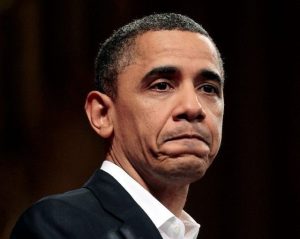

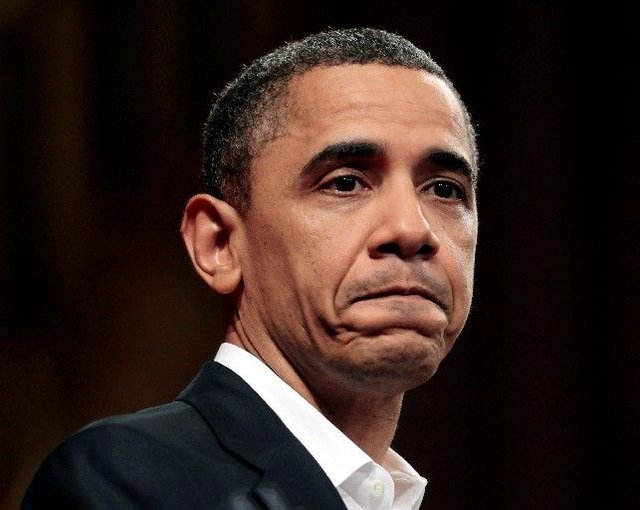

During the 2008 presidential campaign, then Illinois Senator Barrack Obama told an audience at a roundtable discussion at Purdue University in Indiana, “We are constantly fighting the last war. Responding to the threats that have come to fruition instead of staying one step ahead of the threats of the 21st century.”[1] Obama’s comments reflected an often made observation about foreign relations and war that has become almost cliché. Quoted and re-quoted over the years, the refrain ranges from simply “Generals are always prepared to fight the last war” to “Generals always prepare for the last war, while diplomats try to avert the war they fear at the moment.” In whatever form, the statement, like all clichés, contains an element of truth that cannot be ignored. It also contains an implied criticism of decision makers that Obama made explicit: Those making policy should respond to threats by staying “one step ahead.”

His reasoning should hardly be surprising. In article in Foreign Affairs in 2007, Obama argued that “At moments of great peril in the last century, American leaders such as Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and John F. Kennedy managed both to protect the American people and to expand opportunity for the next generation. What is more, they ensured that America, by deed and example, led and lifted the world – that we stood for and fought for the freedoms sought by billions of people beyond our borders.”[5] Clearly Obama saw it as his mission to build on the legacy of these presidential icons. In his inaugural address, the President told the world, “As for our common defense, we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals. Our Founding Fathers, faced with perils we can scarcely imagine, drafted a charter to assure the rule of law and the rights of man, a charter expanded by the blood of generations. Those ideals still light the world, and we will not give them up for expedience’s sake.”[6]

Such comments, as well as international actions, suggest that Wilsonianism is still alive and well in the 21st century, at least at a rhetorical level. That fact was manifested in the logic behind the Nobel Prize committee’s decision to award the Peace Prize to Obama in 2009. Despite criticism that the award was premature or that the President had done nothing significant to merit it beyond talking about his global vision, the committee’s statements made it clear that, even if unconsciously, they embraced Wilsonian ideals. Citing Obama’s “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples,” the committee went on to extol the President’s ability to capture “the world’s attention and give its people hope for a better future.”[7] Unfortunately, a global – or at least a Western – commitment to Wilsonian isn’t necessarily a good thing. As wonderful as it would be to create the world that the 28th U.S. president envisioned and that so many of his successors committed themselves to, most efforts to do so have tended to prove the old adage that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Or perhaps more accurately, it has validated Niccolo Machiavelli’s assertion that it is more important to a political leader’s power that he appear to be virtuous and honorable than that he actually be virtuous or honorable. This is clearly the case with events unfolding in Libya.

The record of the last nearly 100 years speaks for itself, but a few examples will suffice. In 1913, Woodrow Wilson said, “I am going to teach the South American Republics to elect good men!” After 31 years of tyrannical rule, Porfirio Diaz was ousted from power by a younger generation bent on reform. In the chaos that followed, another strong man, General Victoriano Huerta, took control. In words that sound eerily similar to Obama’s remarks about Qaddafi, Wilson told his Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan that he considered it, “his immediate duty to require Huerta’s retirement,” and that the United States would “proceed to employ such means as may be necessary to secure this result.”[8]

The consequence of Wilson’s so-called sense of “duty” was a steady escalation of tensions that eventually included U.S. intervention in Mexico. First Wilson threw his support to Venustiano Carranza in his struggle against Huerta. In 1914, after the crew of a U.S. ship that had anchored in Tampico was briefly detained, the President demanded an apology and when what he received was not to his liking, he sent the Navy into the Gulf of Mexico. He then learned that the Germans were allegedly sending arms to Veracruz in support of the Mexican dictator and ordered American troops to capture the Customs House and impound the cargo. It did not seem to matter that the weapons came from the Remington Arms Company, an American manufacturer, which had shipped the guns and ammunition via Hamburg, Germany, to avoid the American arms embargo to Mexico. Events escalated from there, forcing Huerta from office.

Because Carranza publicly opposed Wilson’s intervention, the U.S. began negotiating with Carranza’s chief rival, Pancho Villa. Wilson eventually reversed himself, recognizing Carranza’s new government, but antagonizing Villa. When Villa attacked and killed Americans in 1916, the United States retaliated by sending General Black Jack Pershing into Mexico to hunt him down the following year. Although they never captured the Mexican outlaw, they did engage in several skirmishes with Carranza’s army. In the end, the situation in Europe drew the United States into World War I and out of Mexico.

The U.S. mission in Mexico had many of the characteristics that give critics of the current policy towards Libya pause. Informed by a vague moralistic agenda, decision makers in both cases failed to understand that although oppression, abuses of power, and even violence exercised by a tyrannical government against its people are awful things, the opposition does not necessarily equate with virtue, reform, or democracy. If and when Qaddafi goes, who or what will fill the power vacuum? Who will the coalition support and for how long? How many Huertas, Carranzas, and Villas are in Libya’s future?

Equally important are the issues we now call mission creep and exit strategy. With an unclear objective like teaching “the South American Republics to elect good men,” it was easy for Wilson to justify political and military intervention, to switch sides from Carranza to Villa and back again, and to send troops into harm’s way ostensibly to capture Villa. The mission kept changing because there was no clear purpose from the beginning. The only exit strategy was what was forced upon the U.S. by more pressing issues in Europe.

Similarly, open-ended statements like that of UN Security Council Resolution 1973 that authorizes member nations “to take all necessary measures … to protect civilians”[9] provide no clear definition of what that means, when the mission can be considered accomplished, and what contingencies exist for dealing with the aftermath of a post-Qaddafi Libya. Indeed, the conflicting agendas of the various coalition members, and of individuals like President Obama, seem unsettlingly reminiscent of Wilson’s flip-flopping on Mexico. For example, while at times declaring that Qaddafi must go, Obama has also said that the no-fly zone and the use of missiles to enforce it have nothing to do with that goal and are designed to “stop any potential atrocities” against the Libyan people. What happens if Qaddafi comes to his senses and stops the atrocities? What if he is toppled and his replacement is just as bad or worse? Diaz was eventually replaced by Huerta, who proved to be just as bad. The vagaries of revolution have a tendency to produce such confusion, be it in early twentieth century Mexico of early twenty-first century Libya.

Of course, there are those who may argue that Libya is different. After all, the United States acted unilaterally against Mexico, but the coalition against Libya is international. Be that as it may, the logic that informed both missions derive from the same rhetoric; or if one wishes to give Wilson, Obama, and the coalition the benefit of the doubt, the same thinking. In either case, it is both dangerous and self-deluding, allowing decision makers to assuage their consciences, justify their actions, all while perpetuating the sort of violence they supposedly deplore.

Another Wilson example is equally instructive. In deciding to go to war in Europe, Wilson told Congress, “”Neutrality is no longer feasible or desirable where the peace of the world is involved and the freedom of its peoples, and the menace to that peace and freedom lies in the existence of autocratic governments backed by organized force which is controlled wholly by their will, not by the will of their people . . . We are at the beginning of an age in which it will be insisted that the same standards of conduct and of responsibility for wrong done shall be observed among nations and their governments that are observed among the individual citizens of civilized states.”[10] One hundred and sixteen thousand Americans lost their lives for that vision. The victors at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, however, were more concerned with punishing the Central Powers. As British Prime Minister David Lloyd George put it, the negotiations at Versailles had more to do with “squeezing the orange until the pips squeak” than implementing the Fourteen Points, making the world safe for democracy, or creating of a victorless peace. Members of the United States Senate were equally unsympathetic. The United States never joined the League of Nations or signed the Treaty of Versailles, and twenty years later the world was on the brink of another global war. As mission creep continues in Libya, who is to say how long support for the international effort will last? If international resolve weakens and Qaddafi manages to remain in power, it is clear he will squeeze the oranges even harder than Lloyd George could ever have imagined.

Of course, many may argue that a lot has changed since the days of Wilson. Military technology, global politics, and shifting economic dynamics to mention just a few. However, the problem is that the logic of U.S. foreign policy has remained fundamentally the same. Examining the record of the presidents Obama held up as models of American global leadership in his article for Foreign Affairs reveals an interesting pattern. The ideals of Wilson’s Fourteen Points were enshrined in the principles agreed to by Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in August 1941. Unfortunately, the American President learned the hard way that while such an agenda may have made sense to American and English sensibilities, it had little place in the calculations of Soviet leader Josef Stalin. At the Yalta Conference in 1945, Roosevelt found it necessary to settle for the vague platitudes of the Declaration of Liberated Europe, which paid lip service to the ideals of the Atlantic Charter, while effectively giving Stalin the control he desired in Eastern Europe.

The trouble with propaganda is those who propagate it are often the only ones to believe it. A benevolent, if bungling, American foreign policy is constantly being trotted out. The lack of planning for the invasion of Iraq and the lack of an exit strategy for Libya in their philantropic endeavours are some of the latest. I even heard it said that the invasion of Libya even lacked an entry strategy.

If we believe that rubbish we will never be out of trouble. The logic of any invasion throughout history has the same simple formula i.e. destroy the country you are invading and take home the spoils, and I am sure that with its history very few countries have as much first-hand knowledge of this as the Americans.

Need I remind the history Professor that Wilson was the President who brought into existence the Federal Reserve System? And who exactly sponsored Wilson?

The same people that sponsored Obama. Who needs the history lesson?

Yes I know some reading these words will dismiss me as a kook, but consider the fact that as Ben Bernanke papers the world with dollars the inflation for the poor of the second and third world sky rockets and revolutions break out. Wars that threaten to topple old orders and bring “democracy” and new orders. Qui bono? It’s certainly not the American people. Or the people of Iraq. Ect.

There is no idealism in Obama’s lofty words, just cold calculation. The Libyan “dictator” has refused to play by the rules from the get go. Further he has not allowed his banking system to be a part of the Western Central Bank system.

It is state owned. Now who might that enrage?

Lastly, America seems quite fine with the throughly corrupt and decadent House of Saud, who have a much more brutal secret police than anything Mr Quadaffi ever implemented. And what about Bharain? That’s off the map even those people want democracy and the US Fleet is yards away as they get carted off to be tortured or worse. As I write the Saud goons are cracking down on the protestors while the US Fleet does…nothing.

And for American readers I will add this. The inflation, pain, and misery is going to wash upon these shores like you had never even imagined. Consider it this way.

For years the US empire bad cop routine that enforced the creation of the New World Order all around the world has decided that you are next. Call it what goes around, karma, God whatever….it’s coming. The financial 2008 debacle was the opening round. Like a vampire that is draining the neck of it’s prey the banks are not done. The public is waking up, still the vampire is running the show. Your whole economy is rigged. Any honest examination will prove that. One debt bomb and they can send millions into poverty forever, though the preferred method is to do it slowly so as to extract more wealth.

If the vampire(the New World Ordure)gets it’s way, which it has so far with Iraq, Libya, and the remains of the United States your children are consigned to a slave like future. There will be absolutely no social mobility and you will be lucky if you are are allowed to work for the masters, though you will never see them. I can assure you from personal experience they live lives of unimaginable luxury. Your favorite celebrity is a pauper compared to their wealth. If you think that history can’t repeat itself think again. And you are not special because you are an American though they tell you that. They will have your sons slay their fathers.

Harsh but effective and loyalty to thier gods are all that matters. Get a clue.

A while back in a purely support capacity way I was able to attend an event where the Bush son was speaking. The people I dealt with were the visible millionaires, and his already picked out cabinet. But before that Bush met with an even more VIP group who arrived in dark tinted SUVS and on this huge grand estate they met in what I can only describe as a type of black marble masoleum. The french waiters told us they were eating there on gold plates, and when Bush came down to the lower group a huge group of CIA types with bulges under their coats swarmed around us. Bushes first joke was how “compassionate conservativism” was giving them all a tax break. Lots of guffaws.

After that I knew that voting means nothing. It was decided way before. Still I had no idea that 9/11 would come or the endless War on Terror. But I knew that I did not like what I saw. So maybe I have a little sense of “history” here.

I sense the same thing now.