English as She Is Spoke was the unfortunate title of a 19th-century Portuguese-English conversational phrase book, for English learners, written by Pedro Carolino. In the translation community, this book has attained almost legendary status, as a cautionary tale of how not to write a language book and how not to translate.

Growing up, whenever I had a difficult school exam coming up, my Italian grandmother would say to me, “nella bocca del lupo” or “in the mouth of the wolf.” It wasn’t the most comforting thing to hear before an exam. But I guess, “break a leg” isn’t much better. One thing that “nella bocca del lupo” and English as She Is Spoke have in common is that they both made a lot more sense in the original language than they did when translated directly into English.

It is nearly impossible for students with a European native tongue to do a word-for-word translation and have it make sense in English. For example, this German sentence would be completely incomprehensible if directly translated: Hemingway betätigte sich nicht nur als Schriftsteller, sondern war auch Reporter und Kriegsberichterstatter, zugleich Abenteurer, Hochseefischer und Großwildjäger, was sich in seinem Werk niederschlägt.

Direct word for word translation: Hemingway busied himself not only as an author, but was also reporter and warcorrespondent, atthesametime adventurer,deepseafisherman and bigwildhunter which self in his work reflected

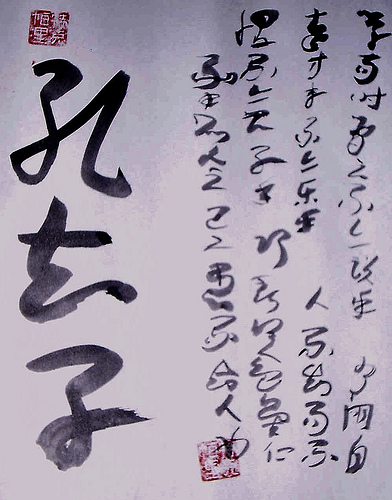

German is one of the primary origins of the English language, and yet the composition of the language is completely different. Can you imagine now, taking Chinese sentences, Chinese brains and Chinese thinking, and simply plugging in English words? The results would be even further from sensible communication.

False Translations

Here are some examples of Chinese words whose common dictionary definition in no way reflects the complex connotations assigned to them by native speakers.

| Wanr | 玩 | Play |

“Wanr” is normally translated as “play”. And in some instances, it does mean “to play”, as a child plays. But it also means to relax, to engage in recreational activities. So if you go on holiday, a Chinese friend might ask you, “How did you play on your holiday?” To which you would answer, “I played well.” Of if you didn’t enjoy the holiday, you would say, “Oh, it was bad play.”

Foreign teachers find it strange when they ask adults what they plan to do on the weekend and they answer, “Play with my friends.”

| Shi | 是 | Yes/is |

“Shi” is commonly translated as “yes” or “is”. And there are certainly examples where this translation holds true, such as “My mother is a doctor,” or “He is my teacher.” But with adjectives, the word “shi” is not used. So a Chinese speaker would effectively say, “My book red colored.” Not, “My book is red,” or “My brother very tall.” Not, “My brother is very tall.”

In other cases where English would use “is” Chinese uses alternative words, rather than “shi”. My house is behind the school. In Chinese would be “My house zai school beside.” Here, “zai” rather than “shi” is used to show location.

Using “shi” as “yes” is even more problematic, as it depends on the question. If someone asks, “Did you eat yet?” You would answer “Not yet” or “Ate”. You wouldn’t answer “shi”. “Do you want to come with me?” You would answer “Want” or “Don’t want.”

Most English speakers would believe “yes” and “no” to be very basic linguistic concepts, or at least expect them to be cut and dry. The Chinese concept of yes and no must be very different from the western concept. By extrapolation, we would have to imagine this carries over into language learning.

| Guanxi | 关系 | “connections” or “relationships” |

“Guanxi” is loosely translated as “connections” or “relationships,” but there are countless articles and even books written on the complexity of “guanxi” and what it means in Chinese society, and particularly what it means for Chinese business. Doing business anywhere, it is better to have connections.

Moving from individual words to sentences, we can see that the Chinese language brain is coming from a different perspective than the English language. Here is an example of a Chinese paragraph from my level-two Chinese book. One friend is telling another how to go to the post office. Obviously, newspaper Chinese would be even more complex. But even with such a low level text, we can see that translation is not just a matter of plugging words from one language into a brain accustomed to the syntax, grammar, and culture of another.

bai yun gaosu ta cong xuexiao nan men wag dong zhou you – ge shizi-lukou, guole shizi-luokou wang bei guai you – suo xue-xiao xuexiao pangbian jiu shi youju.

Remember that this is a preposterously direct, word-for-word translation of the Chinese text, but to illustrate a point: hundred cloud told her from school south gate turn East walk there is a ten street mouth cross the ten street mouth turn North there is a unit study school next to just is post office.

Again, no one would make the error of translating this directly into English, but I have had students say to me, “Teacher, ten month I go to Beijing,” for example, rather than saying “October”, because months in Chinese have numbers, instead of names. Keep in mind that Chinese does not have punctuation. Sentences are extremely long strings of Chinese characters. It takes years of practice to figure out where one idea ends and another begins. This is something you will see reflected in the writing of Chinese students. Their sentences will generally be too long and may include several distinct ideas.

Linguistic Concepts and Features

Chinese words don’t alter for plurals, you simply say “one volume book” (一本书 yi ben shu) or “3 volume book.” (三本书 san ben shu). The word “book” doesn’t change for plural. Verbs are also not congregated. So, in “I go” and “she goes” the word “go” remains the same. This is why students frequently forget terminal “s”.

The concept of verb tense in Chinese is very different from English. In Chinese, “I go to school” (我去上学 wo qu shang xue) and I went to school (我去上学 wo qu shang xue) are identical. In Chinese we can even signal the past by simply adding a past cue, such as “yesterday” or “ten years ago” without changing the verb or giving any other clue that we are talking about the past.

ESL programs are typically focused on production, but if we look at passive skills, listening and reading, we will see that these issues are actually worse in passive than in productive skills. This is because students have had their production corrected time and again by teachers, but no one is looking after the errors they make in passive skills. Students simply don’t hear terminal “s” or “ed” or other features of the language which differ. In an English textbook, I remember a story about an old woman, telling the story of her life. There were grammar cues which told you when the story shifted from the present to the past, but many students missed the cues.

Since the concept of spelling is moot in a pictographic language, the concept of spell checking also doesn’t exist. In the past, when students wrote essays in Chinese by hand, the teachers meticulously inspected every word, to see if even a single stroke were left out. One of my friends once said to me, “I missed one stroke, of a ten stroke character, on the third page of a five page paper, and my teacher caught it.” But today, with computers, it is impossible to miss a stroke (although students could possibly choose a wrong word). As a result, the concept of Microsoft Word spell check is limited to the student’s English papers.

As a university level teacher, I find that, unless the students have attended an international school, they have never written even a single essay in English before arriving at the university. As a result, my class is their first experience with spell check. In my first term of teaching, I was shocked to receive papers with spelling errors. Wrong words, I assumed, would be a given, but how can you misspell things nowadays? After a few weeks, I realized, the students needed someone to teach them what the spell check was and how to use it. Many of the students had turned off the spell checker, because it got in their way. Other students were using pirated versions of Microsoft Word, which didn’t have a spell checker.

There is no capitalization in Chinese so, as a learner of Chinese, it is often hard to pick out the proper nouns. For example, the first two words in the Chinese paragraph above, “bai yun,” represent the name of one of the characters in the story.

Antonio, Enjoyed your article. However, it might have been helpful to your Korean teacher of English if you had explained the concept of “portmanteau words.” In this case, it might have been easier for the teacher to understand that the name “Chunnel” was created by combining elements of “channel” and tunnel. On the other hand, I certainly agree that learners often do not perceive that initial capital letters on words signify names….