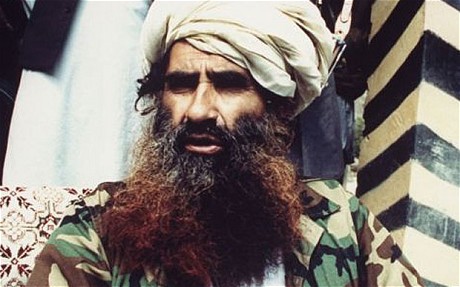

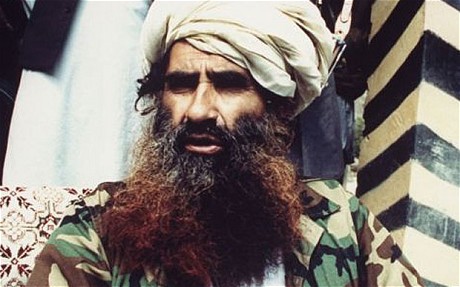

Mujahedeen commander Jalaluddin Haqqani in his base camp near the Pakistani border. (Photo: Getty)

Since the beginning of the Global War on Terrorism, barstool and armchair political savants have often remarked that America created the issue of Al Qaeda and the Taliban by aiding the mujahideen during the Russian occupation of Afghanistan. While this idea is broadly true, the fine nuances are often left to vague shoulder shrugs and abrupt changes of topic when pressed for details beyond bumper stickers and headlines.

America’s involvement in Afghanistan has been pocked by tremendous missteps – but most commonly as diplomats, politicians, and soldiers blindly meander through the cultural minefield, creating a political landscape as scarred as the bombed and blackened mountains of the Hindu Kush. However, no travesty has been more avoidable or iconic than America’s involvement and mishandling of Jalaluddin Haqqani. With American money, training, and armament, Haqqani rose from the dust of obscurity like Frankenstein’s monster upon the alchemy of the late-Romantic era; however, it was America’s lack of humanity, cultural insensitivity, and diplomatic arrogance that soured the monster into the uncontrollable beast bent on the destruction of its creator.

Jalaluddin Haqqani cut his teeth on jihad in the infamous Muslim Youth Organization of Kabul University – a late 1960s jihad-focused group of students modeled after their faculty’s involvement in the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.[1] As the group went underground in the late 1970s, they adopted the name Hesb-I Islami, and declared holy war on the government of Afghanistan. Haqqani at once found himself in the upper echelon of the organization’s war council until the Hesb-I Islami began to disintegrate due to personality conflicts between Gulbuddin Hekmatyr and his political opposites, Professor Burhanuddin Rabbani and protégé Ahmed Shah Massoud. The group was eventually pieced back together under the new banner of Harakat-i-Inqilab, but Haqqani was no longer interested. Rather, as Harakat rose to the forefront of the jihad, Haqqani took note of the revered Islamic journalist, Yunis Khales, who re-established Hesb-I Islami to capitalize on the fatwa for jihad and the name he thought “too valuable to abandon.”[2] Yunis immediately drew hard-hitting jihadists such as Jalaluddin Haqqani, Dost Mohammed, and later the teenage urban guerilla, Abdul Haq, and a young, wealthy Saudi financier, Osama bin Laden, to the fledgling party of Hesb-I Islami Khales.

With Khales, Haqqani was empowered and quickly earned a reputation as a fierce warrior in the mountainous border region of Loya Paktia. His prowess garnered direct support from Pakistani ISI and American CIA who trained and equipped Haqqani’s soldiers with guns and stinger missile systems. His end of the transaction came in the form of a vague measure of accountability to be evidenced in the toll of Russian casualties.[3] Peter Tomsen, the Department of State’s Special Envoy and Ambassador on Afghanistan from 1989 to 1992, had this to say in a recollection to PBS’s Frontline:

[Haqqani] would come to Islamabad for meetings, but he would always be out for more—something to attract more ordnance, more money for himself… And ISI would sit in their offices and tell him, “Well, we’re going to provide you this much for this many men, and we want you to take this particular offensive.”[4]

When asked if it were the CIA who built a lot of Haqqani’s capacity, Tomsen responded with a simple, “Yes.”[5] It would be easy to say that the intelligence community could not have predicted Haqqani’s future, but it was clear that he was no friend of the West as the 1980s and Russian occupation drew to a close. Haqqani sidled closer to radical Arab wahabbists—a fanatical faction of Islam that believes only in a strict Sunni interpretation of the religion from the time of its creation. He spent more time in Mecca fundraising for independent revenue sources, spoke Arabic, looked upon the west with disdain, and embraced Deobandism, a similar form of Islam to wahabbi. When war reporter Robert D. Kaplan went to Haqqani’s Pakistan-based compound late in the war, he was shocked by cold, angry eyes of Haqqani and his Arab compatriots, and their open lack of hospitality, which is counter to the typical hallmark of Pashtun tribal etiquette. The radical anger was stark against the backdrop of Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier Province, where mujahideen commanders depended on journalists to publicize their causes. Kaplan took the hint and promptly left.[6] This was hardly the behavior that once earned Jalaluddin the honorific of “goodness personified” by Texas congressman Charlie Wilson.[7] The signs were beginning to show a darker side of Jalaluddin Haqqani – as dark and untamed as his long, black beard that seemed to highlight the rage in his eyes. Perhaps it was simply the effects of a man immersed in constant war for over two decades, or possibly the psychological toll of a man turned into a malign function in the hands of foreign nations.

None of that seemed to matter to America’s narrow focus of toppling Communism. They simply allotted Haqqani more war materials based upon the observation of CIA handlers that, “[Haqqani] could kill Russians like you wouldn’t believe.” Those materials and money were then matched by Saudi intelligence in their One-For-One policy.[8] Everyone wanted a piece of him – to use him. The relation between source and handler should be closer to courtship than clinical detachment, and it should resemble more a friendship than slave and sociopath. Perhaps Robert Baer, recipient of the CIA’s Career Intelligence Medal, put it most eloquently regarding recruiting agents in that corner of the world when he said, “You don’t recruit an individual; you recruit families, clans, and tribes.”[9] A handler should be immersed in his source, and vested in his family. Though three different nations handled Jalaluddin Haqqani, each seemed only interested in weaponizing him to achieve their national interests. Without that personal investment, America would never be particularly clear of his crosshairs – especially when Washington lost interest in Afghanistan and the flow of money abruptly stopped with a nation left in shambles.

After the Russians fled and the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan fell, Haqqani maintained his area along the eastern border of Afghanistan where he established a prominent madrassa in north Waziristan, Pakistan known as Haqqania which supplied much of the fodder for the Taliban ranks and a great deal of the momentum for the early movement.[10] In 1995, arguably at the behest of Pakistani ISI, Haqqani himself joined the Taliban and took command of the front line outside Kabul. Jeffery A. Dressler of the Institute for the Study of War, contends this was likely a play by Pakistani ISI to steer the Taliban to meet Pakistan’s objectives as the agency abandoned their long-time proxy, Gulbuddin Hekmatyr.[11] However, much of that evidence is shrouded in secrecy and classifications. One thing is certain: the ISI had finally backed the winning horse. Whereas Hekmatyr battled Ahmed Shah Massoud of the Northern Alliance for control of Kabul in a fierce battle that claimed thousands of civilian lives over the span of a couple years, Haqqani’s forces decimated the Shomali Plains area outside of Kabul, which enabled the Taliban to seize Kabul and maintain the majority of the country.[12] Pakistan had finally gained the strategic depth they desired for defense against the paranoia of an invading Indian army, and Mullah Omar, leader of the Taliban, ousted the last of the remaining interim government of the mujahideen. Mullah Omar promptly rewarded Haqqani with the position of Minister of the Border and Tribal Affairs, though this proved to be an arbitrary move to satiate the frustrations of Haqqani’s men with the leadership from Khandahar. Despite the position, Haqqani, a Ghilzai Pashtun of the Zadran subtribe, was left out of the largely Durrani Pashtun decision making of the Khandahar inner-circle. Haqqani felt an Islamic Republic would better suit Afghanistan, and was not fond of the arrogance of the Khandahari leadership. Though he occasionally let these sentiments slip in private to close friends such as Maulavi Saidullah, he stayed loyal to the Taliban and its leader.[13] This perception of alienation could have proven to be excellent motivation for co-opting Haqqani and returning him to the fold of an experienced handler capable of re-establishing an effective rapport. Unfortunately, this altruistic capital would be squandered by the bravado of blind patriots and Washington jingoes.

In early December of 2001, Coalition Forces and Northern Alliance Afghan soldiers stormed Haqqani’s homeland in search of Osama bin Laden at the site of the mountain fortress known as The Lion’s Den. Though 250 Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters were reportedly killed, Osama bin Laden managed to escape.[14] Jalaluddin Haqqani hid his old friend in a house outside Khost before smuggling him into Pakistan with his family, though Haqqani himself stayed behind to broker a deal with a nation that once regarded him so highly.[15]

Testing the tinsel strength of their rekindled relationship with an angry America, Pakistani ISI urged the CIA to accommodate Haqqani and perhaps give him a token position in the newly formed government.[16] Had America listened to Pakistan, not only could their relationship perhaps fostered into a true alliance, but the next decade of military involvement could have been drastically different. Jalaluddin could have stabilized the Afghan border region early in the conflict, and Pakistan could have become a greater partner in the War on Terrorism clearing and reinforcing the border from their side of the country. Unfortunately, the Department of Defense and Washington in general were deafened by the dull thunder of war drums and anger of the American populace. The deal offered to Jalaluddin Haqqani was unconditional surrender, betrayal of Osama bin Laden, an all expense paid trip to Guantanamo Bay, and interrogation. After an indefinite amount of time, he would be allowed to return to his home.[17] Honor is perhaps the single-most important virtue of a classic Pashtun tribesman. He will kill his daughter and maim his mother to retain it, and after suffering an insulting offer like this he is bound by his tribal code to seek and achieve vengeance or place his descendents forever after in a state of honor bankruptcy, or daus, until the blood feud is satisfied. So began Jalaluddin Haqqani’s war against America.

Jalaluddin Haqqani’s son, Sarajuddin, was born to Haqqani’s Arab wife, which strengthened his ties with Riyadh and insured a legitimacy among his future descendents. Despite his sacred blood, as a boy Sarajuddin reportedly cared more about his appearance than his father’s work. An ISI officer and friend of the family claims, “He didn’t take to war,” and he often referred to the Taliban as “heavy-handed” and “dogmatic.”[18] However, shortly after his father was insulted, Sarajuddin experienced a religious awakening and grasped the reigns of the Haqqani Network as they began to slacken in Jalaluddin’s aging grip. From 2002 to 2006, Sarajuddin reconstituted the network and rekindled the Taliban’s might through arduous fundraising and solicitation of foreign manpower. Though the network enjoys some autonomy, they repeatedly swear allegiance to Mullah Omar and his dream of an Islamic Emirate. Even as recently as October 2011, Sarajuddin said this to BBC regarding his relationship with the Taliban:

Ameerul Momeenin [Leader of the Faithful] Mullah Omar is our leader and we follow him, we have responsibility for certain areas within the Islamic Emirate’s administration and accordingly follow instructions. In every military operation, the Emirate gives us a plan, guide and financial support. We conduct it thoroughly. There is no question of a separate party or group.[19]

Responsible for everything from the bombing of India’s embassy in Kabul, to shooting down an American helicopter carrying Navy SEALs, to allegedly assassinating Burhanuddin Rabanni of the High Peace Council, Sarajuddin has shifted the nature of jihad in Afghanistan and the jihadists that have waged the struggle since the Haqqani Network came fully online in 2008. Perhaps one of the most evident cases occurred in late August of 2010 when Forward Operating Base Salerno received mortar rounds and recoilless rifle fire as machine guns opened up on one the largest outposts in Khost. Thirteen Haqqani fighters wearing suicide vests and night vision goggles maneuvered to the perimeter fence in the pre-dawn hours and breached near the airfield. Two years later, in June of 2012, a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device pulled near the perimeter wall and detonated, leveling a good portion of Salerno’s defenses as fourteen Haqqani operatives armed with machine guns, rocket propelled grenades, and suicide vests poured in through the breach.[20] Sarajuddin brought strategic focus to once tactical level ingenuity creating spectacular attacks that often garner international attention. The dynamic effectiveness of the Haqqani Network has since forced American policy beyond the placement of his group on the United Nations’ international terrorist blacklist, but redefining what victory in Afghanistan entails.[21] Perhaps the most telling reason why can be glimpsed in Sarajuddin’s warning to Pakistan:

Our advice for the people and government of Pakistan is that they should carefully note the American double standard and irreconcilable policy. They should give precedence to their national and Islamic interests. They should take [it as a given] that the Americans will never be satisfied until they loot them completely.[22]

Sarajuddin’s observation of irreconcilable policy and vampiric drain until there is nothing left is reminiscent of the manner in which his father was used by the American government, and echoes of the severance package offered in the aftermath of the assault on the Lion’s Den.

Though casualties rise, the war winds down over a decade since the first bomb fell. The border remains porous, and the Pakistani government has never given an honest attempt at making a single arrest in northern Waziristan Province, the current stronghold and location of Haqqania, or stabilizing its border with Afghanistan. It has been over a decade since America expressed disinterest in a continued relationship with Jalaluddin Haqqani, though he persists in reminding them what they originally saw in him, what they created of him, and the day they turned their back on him. These stark reminders should serve as a cautionary for caustic policy making based upon bravado and anger exacerbated by cultural ignorance and diplomatic irreverence. Haqqani is a reminder of the humanity that must exist in human intelligence. And as strategic locations explode and erupt in the constant din of machine gun fire with a seemingly endless stream of martyrs, Jalaluddin Haqqani brazenly stands as a reminder that defiance has cold, dark eyes and wears a long, black beard.

References

[1] David B. Edwards, Before Taliban: Geneologies of an Afghan Jihad (Los Angeles: University of California Press,2002), Kindle edition, chap 7.

[2] Ibid,

[3] Jeffery A. Dressler, “Haqqani Network: From Afghanistan to Pakistan,” Afghanistan Report 6 (2010): 8.

[4] Peter Tomsen, Return of the Taliban Interview, Frontline, PBS, July 20, 2006.

[5] Ibid

[6] Robert D. Kaplan, Soldiers of God: With Islamic Warriors in Afghanistan and Pakistan (New York: Random House, 2001), Kindle edition, Introduction.

[7] Dressler, 8.

[8] Ibid, 9.

[9] Robert Baer, See No Evil: The True Story of a CIA Ground Soldier in the War on Terrorism (New York: Crown, 2002), Kindle edition, chap. 6.

[10] Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), Kindle edition, chap 16.

[11] Dressler, 9.

[12] Peter Tomsen, Return of the Taliban Interview.

[13] Dressler, 9.

[14] Guy Walter, “How the World’s Most Wanted Man Made Fools of the Elite Troops Who’d Trapped Him in His Mountain Lair,” The Mail Online, April 30, 2011, www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1382011/.

[15] Joby Warrick, Triple Agent: The Al Qaeda Mole Who Infiltrated the CIA (New York: Random House, 2011). Kindle edition, chap. 9.

[16] Ibid, chap. 9

[17] Ibid, chap 9

[18] Dressler, 9.

[19] Sarajuddin Haqqani, Interview by BBC, News South Asia, BBC, October 3, 2011.

[20] Bill Roggio, “US Troops Repel Suicide Assault on Base in Eastern Afghanistan,” The Long Wars Journal. June 1, 2012, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/06/us_troops_repel_suic.php

[21] Al Jazeera, “UN Adds Haqqani Network to Terrorist Blacklist,” Al Jazeera. November 6, 2012, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia/2012/11/20121166251166331.html

[22] Haqqani, Interview by BBC.

But an alternative simple way to make confident which not often covered come upon oneself utilizing a set of fake oakleys sunglasses solar shades is by inspecting a packing options which those sun cups are rescued in. The thing about fake oakleys sunglasses shades is them to come in lots of different types for both men and women.