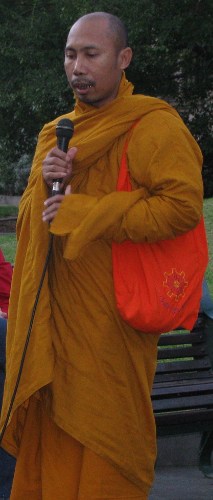

U Tay Zaw is wrapped in a traditional monk’s attire of saffron and maroon coloured robes. He clears his throat and shows me what he has learned in his most recent English class. It is a phrase that he and 12 of his colleagues have constructed. Eleven of the students are from Burma, his homeland, and they all share similar stories of fleeing under persecution from the military.

Behind the monk reads a message written on a whiteboard with a faded marker. It says, “In the world there is much unhappiness, man-made or natural disaster, war, anger and disease”.

If this sentence is designed to reflect the current political, social and humanitarian turmoil in U Tay Zaw’s homeland, then the faded writing represents just how strongly the message is imprinted in the minds of the public, based on the ability of receiving accurate reports from within Burma.

This is a land where all foreign media outlets are banned. A report released by the Thai-based human rights group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) by April 2009, 50 media activists were held in prisons around the country. These are just confirmed cases.

“Our language tutor asked that we make up a sentence based on how we feel, so the students put this together,” U Tay Zaw says.

Many individuals from Burma living in Australia all have a story of survival to share in which the common theme evolves around being on the run from the military regime.

U Tay Zaw lifts up his robe and shows his ribcage before recounting the first of many instances in which he escaped with his life.

“Two other monks and I were forced to dive into the river when military soldiers were firing at us. I hit a pipe when I entered the water, was knocked unconscious, and broke my ribs.”

U Tay Zaw (David Calleja)

U Tay Zaw is a member of the ’88 Generation’. Like many Burmese community members living in Melbourne, U Tay Zaw’s taste for political activism began shortly before the first of Burma’s many dark hours in recent history. As a 24 year old in Mandalay, he became heavily involved during the 1988 People Power revolution which saw monks, students, civilians and even some members of the military take a stand against the leaders of the junta.

“I was a member of Red Garuda [named for a mythical half human creature] group in Mandalay. My job was to protect civilians, students and other monks. At the same time, I preached to members of Burma’s non-Buddhist minority groups not to riot, just demonstrate. They obeyed these requests.”

Surveillance from military intelligence members, police officers, rich civilians with high connections to the government and poor people desperate for money was a part of daily life for U Tay Zaw. With tens of thousands of people, including monks, students, civilians and even police and army members dissatisfied with the military regime’s leaders taking to the streets across Burma in human waves, the country was brought to a standstill for 40 days.

Then suddenly, upon orders from the regime’s leaders, soldiers opened fire on the streets into crowds of people. Three thousand unarmed civilians were massacred.

U Tay Zaw went into obscurity for a number of years, hotly pursued by the military. He trekked through forests and sought refuge in monasteries. Along the way, he gave speeches about Buddhist philosophy, politics and distributed anti-government flyers at night when the military was not on patrol. U Tay Zaw’s movements were constantly monitored by spies but earned the trust of village inhabitants.

Assisted by monks unions, members of the National League for Democracy and other opposition groups, he occasionally distributed pro-democracy and anti-junta pamphlets in nearby cities, a move which saw the monk apprehended by the military.

In the run-up to the country’s ill-fated 1990 elections where the military refused to accept defeat at the hands of the National League for Democracy, U Tay Zaw was arrested by military authorities and incarcerated in Gyopin Oat District police station for seven days.

“Back then, Mandalay had a reputation of being a home for monks with a political agenda. The authorities assumed that because I had just recently arrived from Mandalay, I was a troublemaker.” He then proceeds to climb onto the table before sitting upright and placing his legs in front of him, showing me the seated position in which he was forced to adopt. Pointing to his shins, he begins to describe the ordeal he faced.

“My ankles were in shackles and I was beaten with a padouk [a 3 feet long hard wooden stick]. Every time officers asked me a question, I was struck hard. Officers belted my shins, threatened me with 10 years imprisonment, shone bright lights in my face, and kicked and punched me in the back.”

This treatment has left U Tay Zaw with a physical imbalance. But it is the psychological scars that bear testimony to survivors of politically motivated torture in Burma. He jeopardised his neutrality by criticising the junta over a water and dam construction project in Myawadi, Karen State. He encouraged civilians to protest against what he felt was an injustice towards the people living in the town.

By refusing to remain silent, U Tay Zaw became a target of hatred for the authorities along with other civilians in the town. “They tried to link me with the Karen National Union (KNU) and other opposition groups,” he says. Burmese army members blocked civilians from delivering alms to him. They also attempted to force him to deliver a speech, telling everybody not to oppose a water and dam construction project and not to plan any demonstrations.

“In Burma, monks are handed a piece of paper by members of the military regime and are pressured to read it word for word. If a monk does not obey the authorities and tries to add in their own words or feelings, then the authorities will not give any food or medicine to any monk. They will also cut off all electricity to the town.”

I have yet to read it but hope that it will be nice and informative.

Thanks.

is possible send to me

Hello Abumahiya. Thank you for your interest in my article, I appreciate it very much.

I am very interested in your thoughts on what the article says. Please email me at: david_calleja@foreignpolicyjournal.com and provide me with some feedback. In your email, please include the reason why you wish to use the article and where you intend to post it. Thank you and I look forward to hearing from you :)

Abumahiya, after consulting with relevant parties, unfortunately I cannot send a copy of this article.