To salvage any sort of credibility and to begin to dispense justice, the ICC could still tackle the issue of bias by considering issuing arrest warrants for counterparts of Kenyatta and Bashir in the rest of the world—say, Netanyahu.

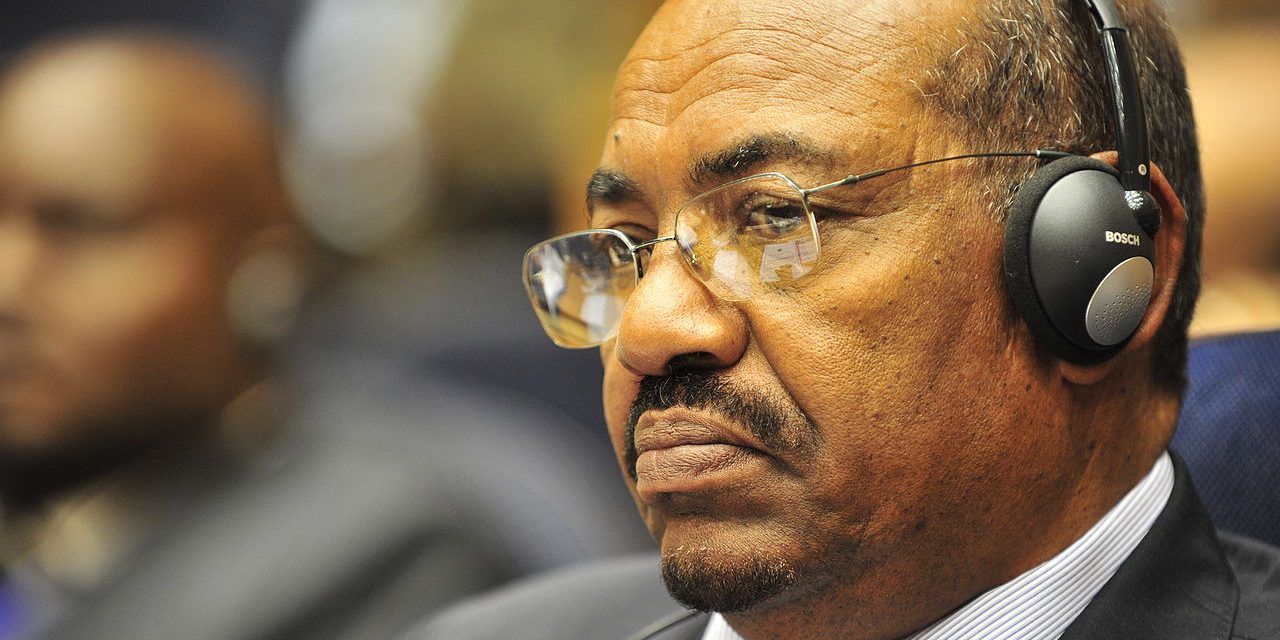

South Africa’s refusal to execute the ICC arrest warrant for Sudanese President Omar Bashir on charges of genocide in Darfur leaves many ordinary Africans simply embarrassed. A vocal minority supports the claim made by African leaders that the ICC is biased against Africa and blind to evidence of war crimes committed by non-African heads of state such as former US President George W. Bush, former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Uhuru Kenyatta declared in 2013 that the ICC “stopped being the home of justice the day it became the toy of declining imperial powers.” Charges against him for crimes against humanity had to be dropped after witnesses withdrew or became untraceable. President Museveni of Uganda has since urged African States to pull out of the Rome Statute arrangement. The squeaky clean Ian Khama, President of Botswana, an early supporter of the Bashir indictment remains silent on the current controversy.

Observers were therefore unsurprised when Bashir was able to attend the African Union Summit in South Africa on June 15 and later to fly out undeterred by the South African law and order apparatus even while Judge Hans Fabricius considered the legal basis of his detention.

Ban Ki-moon’s plaintive appeal to signatories of the Rome Treaty to respect their obligations was necessary, though pathetic; it is clear that contempt is the overriding emotion felt amongst the parties concerned. Two questions arise. First, if the Court is biased, does that mean that African leaders should not be investigated and charged? Secondly, why do African leaders not correct the imbalance in charges by initiating their own proceedings under universal jurisdiction?

It has been persuasively argued that state parties to the Rome Statute need not wait for the Prosecutor of the ICC to initiate investigations but are in a position to set up regional tribunals and apprehend and try suspects in specific cases. However, rather than attempt that, African heads of state receive the suspects with relish: Tony Blair became an advisor to the President of Rwanda, and Benjamin Netanyahu has made a deal with President Museveni to receive African asylum seekers (Israel refers to them as infiltrators) expelled from Israel in return for arms.

While rejecting all claims of systemic abuse, torture and murder of Iraqi’s by British troops between 2003 and 2008, UK Attorney General Dominic Grieve has pledged cooperation with the ICC which has reopened a preliminary investigation in to the case. Neither Grieve nor Andrew Clayey, QC, head of the courts martial authority, believe the abuse was systemic or condoned by senior officials and therefore warranting ICC intervention. In fact Cayley has already stated that civilians such as former Labor defense secretaries Geoff Hoon, John Reid, Des Browne and John Hutton are unlikely to be tried for war crimes.

The United States simply refused to ratify the Treaty, which it signed in 2001. Instead, it has sought bilateral immunity agreements with some countries in which it has military interests, to exempt American troops and contractors from ICC jurisdiction and allow their repatriation to their own countries for further management. Uganda is a case in point. The agreement signed on 12th June 2003 reads in part,

2. Persons of one Party present in the territory of the other shall not, absent the express consent of the first Party,

a) be surrendered or transferred by any means to the International Criminal Court for any purpose, or

b) be surrendered or transferred by any means to any other entity or third country, or expelled to a third country, for the purpose of surrender to or transfer to the International Criminal Court. [1]

Similar agreements have been signed with 34 other African countries (excluding Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Somalia and South Africa.) and many Asian ones. The US’s attitude may be a result of the shock it received in the 1960s when newly independent African states were admitted to the UN General Assembly and proceeded to vote against the US’s preferred positions;, for example, on their active opposition to the elected leader of Congo and seating Communist China’s delegation. At the time, the American reaction was extreme:

The President [Eisenhower] said one of our most serious problems soon would be the determination of our relations with the UN. He felt the UN had made a major error in admitting to membership any nation claiming independence. Ultimately, the UN may have to leave U.S. territory. [2]

One would almost be encouraged if it were to emerge that our leaders have not merely found themselves wrapped around the axle of foreign relations but are taking very calculated steps—some in their own personal interests perhaps—but considered and not accidental. Evidence of this may be found in a memorandum of a consultation between senior British and American civil servants on their policies towards African countries in 1973.

On a rather hopeful note, Le Quesne [Deputy Under Secretary, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Britain] said that African countries are coming to the conclusion that foreign policy is more than UN resolutions. They are beginning to recognize the difference between a government’s public face and its private face. The Algerians are a major exponent of this more realistic approach to foreign affairs and the Zambians are coming to learn it. (Some trains, for example, are still surreptitiously crossing the Rhodesian border [in violation of a trade embargo against apartheid South Africa] despite Zambia’s public insistence that the border is completely closed.) The Kenyans are also being hard-headed and realistic. This new trend toward realism is to be applauded. [3]

There we have it. What on the surface seems like ineptitude is actually a skill to be applauded. Looked at in the light of realpolitik, it appears it is the ICC and its Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, the UN and Ban Ki-moon that are out of step.

To salvage any sort of credibility and to begin to dispense justice, the ICC could still tackle the issue of bias by considering issuing arrest warrants for counterparts of Kenyatta and Bashir in the rest of the world—say, Netanyahu.

Gaza 2014 is the one ICC Situation that requires minimal effort to investigate, its constituent atrocities having been broadcast live for much of the 50 days of the attack and documented by respected international organizations. The Dahiya Doctrine on which Israel relies for its foreign policy in Palestine and other Arab countries is a publicly-announced one, and amounts to a Final Solution to the issue of lebensraum in Israel and Palestine. Its author, Major General Gadi Eizenkot, and promoters, Ehud Olmert, and Colonel Gabriel Siboni, would seem to have at least a prima facie case to answer.

Notes

[1] Source: Georgetown Law Library (current as of December 2009).

[2] Source: Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XX, Congo Crisis, Document 4, Editorial Note. See also Foreign Relations 1958-1960, Volume XIV , Doc. 29, Report of the Conference of Principle Diplomatic and Consular Officers of North and West Africa, Tangier, May 30-June 2, 1960.

[3] Source: Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976 Volume E–6, Documents on Africa, 1973–1976, Document 3 Memorandum of Conversation, London, March 15, 1973

It is a shame, when this Bashir continues to wage genocide of black africans and funds and supports the islamic jihad on the kaffirs in Africa. It is the blacks who were destroyed, however, blacks are so indoctrinated against the whites by the muslims that they cannot see the trees for the forest. South Africa is a criminal government itself too, having stolen 700 billion in 20 years. Perhaps much of the money is channeled to fund isis too.

— non-African heads of state such as former US President George W. Bush, former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.–

At least the present ICC and UNO will ever take a step to try these three

even in absentia. Lady Justice has no eyes and no color but simply ears – hears and gives the decision. Unfortunately we do not have such an eyeless and colorless Lady.