The fall of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali has resonated across the Arab world, and in particular among young Middle Easterners, the majority of whom have lived under authoritarian rule for their entire lives. Tunisian symptoms – inflation, unemployment, social injustice, and a lack of political liberty – are virtually present in all other Arab nations, and thus there is a growing concern among Arab and Western commentators alike about the possibility of another regime fall and the extent to which the current instability could be exploited by radical Islamists.

Although there are good reasons – dissimilar social composition and political history – to believe that these protests will not mean that various Arab Kings and Presidents will experience the same fate as President Ben Ali, there is an important lesson for western policymakers in what seems to be Arab states’ appeal to Islam in order to facilitate their efforts in defusing the current social turmoil in their societies.

On January 19, Mohammed Rifa al-Tahtawi, spokesman of Al-Azhar, asserted that “sharia law states that Islam categorically forbids suicide for any reason”. Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s top Muslim authority has branded the act of self-immolation a “great sin”. Islam indeed prohibits suicide but, given the timing and wordings of these statements, it seems that these declarations are delivered at the request of Arab governments, which in turn provides one with a valuable clue on the role of Islam in Middle East politics.

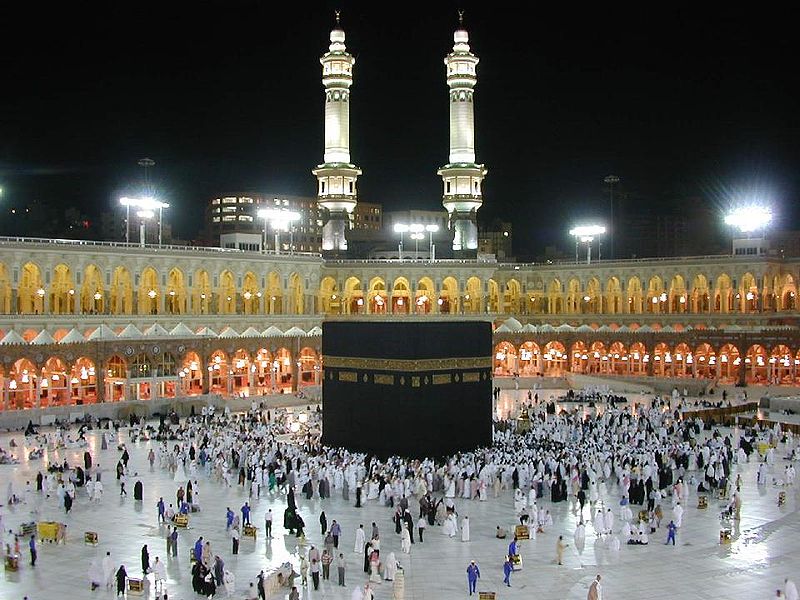

Islam is a powerful socio-political force in the Muslim world, with an extraordinary capacity to generate a language of justice. Its capability to function as an integrative force, thereby establishing consensus on national issues in combination with deeply embedded Islamic consciousness in Arab societies, make Islam a precious political currency with which Arab regimes can convincingly justify their hold on power, resist popular calls for change, keep the society calm, and expand their influence abroad.

As such, the commonly held assumption in Western societies that the greater visibility of Islamic values in the public arena and Islamization in general are the works of Islamic movements is indeed misguided. Obviously, Islamic movements can play a critical role in pushing regimes in the direction of Islamic politics, but a more comprehensive understanding of the role of Islam in the politics of Arab societies requires a sharp focus on the state as an Islamic actor on its own. This is so, given that states have played a critical role in embedding Islam in politics both as a reaction to societal pressures, as well as a means to preserve their power. This is evident in construction of Islamism as both a threat and opportunity, depending on the political needs of regimes at any given time.

This is why Western policymakers cannot logically expect extremists to stop manipulating Islam for political gains when their own allies have been doing just that for decades. More importantly, these recent references to Islam serve as a reminder for why secularism or separation of Islam from politics is neither the solution to radicalization nor a possibility in the Arab world. Secularism can indeed further radicalize Islamic movements by providing Arab regimes with yet another excuse to limit the political space under the banners of national security and counter-terrorism. Interpretations of Islam have been disputed since the 7th Century, as epitomized in the Shia-Sunni rivalry, and hence Islam will remain a political force for as long as there is no institutionalized consensus on its relevance to the daily life of Muslims in the 21st Century.

Thus, governments appeal to Islam in order to calm the public anger should not be surprising. What is surprising is the rigidity of Arab governments in their adherence to the same old tactics instead of using the momentum to initiate reforms. Arab states, like states in other parts of the world, seek to establish and maintain hegemony over their societies and in the process they do not miss a chance to employ Islamic norms to their own advantage. The problem, however, is that in doing so they are rather awkwardly motivated by self and family interests, as opposed to national interests, which has led to the emergence of a great gap between their concerns and those of their citizens.

The loyalty and obedience that are deeply rooted in Arab nations combined with a sense of quiet entitlement has led to a situation in which economic well-being comes from social inclusion, rather than productivity. There are obviously exceptions, but those are the minority. This problem is further exacerbated by the political systems in the Arab world, which combine authoritarianism with limited, private consultation, thereby drastically reducing the channels of communication between the public and elites. Motivating people is a risky business with unpredictable results, and government officials seem uncomfortable with the possible trade off that they might have to make between their ability to hold on power and inspiring people.

Finally, there is the problem of corruption and a firm belief among the public that the keys to success are connections and privilege rather than creativity and competitiveness. Rules and regulations, as they appear “on paper,” are not applied consistently. At the same time, many locals and foreigners complain about lack of transparency in private and public sectors, uncertainty about regulatory policies, and unfair competition practices, which collectively constrain businesses by reducing the incentive to comply with regulation and the desire to invest.

As such, recent comments by Hilary Clinton on lack of political and economic reforms in the Middle East are to be welcomed with a sense of optimism. However, American officials should spare a moment and reflect upon U.S. policy in the Middle East. There are always two sides to a story. U.S. backing of Arab governments through consent – the Persian Gulf subregion – or provision of financial aids – Egypt – has indeed played a role in deepening the current crisis. The U.S. is certainly in a position to use its aid packages and security guarantees as a stick to encourage Arab leaders to reform their polities and markets, not least because their stability serves as the pillar of American strength in the region.

U.S. officials can tour the region and deliver compelling speeches on the need for immediate political and economic reforms in various Arab countries. And the Arab public, surly the middle class, will listen to them enthusiastically. However, the question is whether the American government is ready to listen to their message: less talk, more action!

The US govt’s role is to defend its interests. Not to be the moral leader of the world. Nor is it Egypt’s or the Saudi family’s role to be moral leaders of the world but rather to defend their interests. Likewise, it is the role of citizens to defend their interests against corruption, selling out of national resources, and the protection of individual liberties from political, economic, and social controls. The US has reduced its economic support for Egypt. Egyptian govt has continued to take military support from the US. One could then argue, that the rise of democracy in Egypt, if that is what is happening, is because the US stopped subsidizing the autocracy of Egypt and allowed the socio-economic chips to fall when the Egyptian govt was incapable of delivering governance. This, then, would be an argument that the US economic and social aid by the US promotes / subsidizes failing states. (note this not the military aid) Thus, by action, we would interpret, remove social based aid to the rest of the world and let their leaders fall. I am not sure that is the type of action the US should do.

If, on the other hand, the islamic world is expecting the US to overthrow the islamic world’s ancestral leadership, then let that be the overt statement – we, the islamic world, want the US to rescue us from the medieval government left to us by our ancestors.

On the role of islam, christianity was a politico-religious institution until the last two centuries when the people of Europe and the Americas rejected the political role of christianity. Likewise, until the islamic world rejects the political force of islam, it will remain a political force. For both goo and evil. When islam can cleanse itself of the political nonsense of materialstic life, it will be a reasonable target as any other group for blame and praise. And, like any other group, reject blame and accept praise as per its political needs. One day it will say it is the way for women’s liberation, another it will say it keeps women in its place. One day it will say it supports minority religious rights, another it will tear down idols of minority religious groups in Mecca. …

Good persons, whether muslim, christian, hindu, buddhist, or atheist will want to increase human freedom beyond the category of groups. In a setting of political chaos, the question will arise, who gains power? Those muslims, christians, hindus.. that want to prevent the minority from exercising their conscience of dissent or those that want to gaurantee the minority a bill of rights equally held amongst men, women, muslim, christian, hindu, buddhist, animist, atheist, white, black, orange… The role if islam will be to mobilize the followers to become good persons or to become persons that hate the other. That is the challenge before islam in the Arab streets. I hope it will choose the first.

sorry:

When islam can cleanse itself of the political nonsense of materialstic life, it will be a reasonable target as any other group for blame and praise.

should read: Until islam can cleanse…

On a further note, it was twitter, the internet, etc that helped sparked a communication of disempowered persons around the world. Much of that is due to US companies and policies. The infrastructure for communal action, based on the democratic principle of freedom of opinion and press are also exports of the much maligned west. The US and others, each has good and bad. Black and white thinking, originating in the west or the east, is the real problem confronting humanity: the right government, the right religion, the right opinion… Those constructs are the problem. Can islam, as a moral teaching, fix that – no longer to believe in infidels, to believe in the hated of god…?